It was May 4, 1944, a Wednesday between Pesach and Shavuos (Jewish holidays), the Hungarian Gendarmes (police) broke into our house. They said that we should pack our things, not take suitcases, and be at the school yard in a half and hour. We packed whatever we could and bundled what we had in sheets. Wednesday is the market day in the community. When we got to the schoolyard, we look around and we don’t see our mother. My father asked me where’s mommy, no one knows. The four boys were together with my father. Everything happened so fast, I didn’t even get a chance to daven that day (say morning prayers). My father noticed mother’s not there. Finally she came. Before she had anything to say when my father asked, Wie ost ge vesen, (Where were you? in Yiddish). Before she was able to say anything, two Gendarmes came and said we are looking for Mrs. Pasternak.

They took her away, we were shocked. They took her to their headquarters for a good hour. When she finally came, back, she said, I went to see Mrs. Siegfried, a German woman who was a friend of my mother, they grew up together, they went to school together. She was the pharmacist who we dealt with for years. I gave her our money. I said to her listen, I don’t know what will happen to us. If the children come home, give the money to the children, if they don’t come home, then keep it. She turned our mother in. They were very close, they grew up together. I don’t remember seeing any marks on her face from the interrogation.

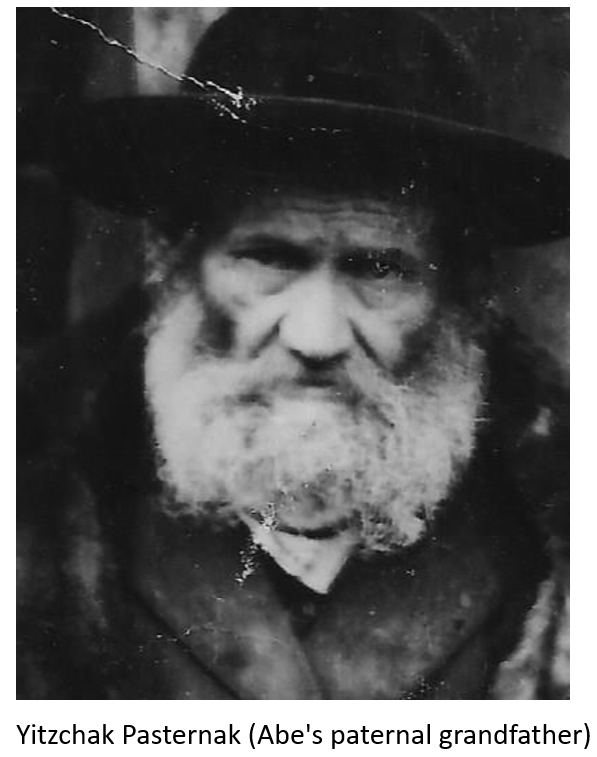

We were there, there was no food, and we stayed there till it got dark. Finally three wagons, horses and wagons arrived. They told us get ready to go. They marched us and the older ones went in the wagons. We walked all night long till we got to an open field, we must have marched 30 km (18 miles), we saw people, people, people, people in an open field. We asked how long had they been there. We learned that some people had been there for one month in that open field with no shelter, no nothing. They gave us some food, but we had to try to get more food from the farmers. Farmers would come and exchange food for clothing and money. We were there three weeks. My father was a religious man and had a beard. He was made to shave it off. He was standing next to my mother and she asked where’s father? My mother didn’t recognize him; she almost fainted when she saw him. We were forced to live like animals, no shelter; the younger people dug fox holes for latrines. This was May 4, 1944, I was 20 years old. There were maybe over 1000 people there. We lived like animals, there was no shelter.

I was taken to work; when I came home sometimes we had food, sometimes we didn’t have food. I remember it was Erev Shavuos, (the Jewish holiday that commemorates the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai) at the beginning of the holiday and then all of a sudden, German jeeps came in. They started to scream and yell, we had to go some security fence of some kind, “Jude to the trekke!” When we first came to the field, we saw these boxcars, it was a railroad spur. We didn’t know what the boxcars were for. We thought it was for the Germans because they were being kicked back by the Russians. They marched us to the trains and loaded us up. We found out it was to transport us.

They marched us to the trains and put us into the boxcars that Erev Shavuous. They loaded us up, 70-80 people in a boxcar. After the war, I checked the size of those boxcars at the United States Holocaust Memorial Center in Washington; they were about 30 feet in length and 8 feet wide. Men and women were mixed in together. There gave us two buckets for waste products and they locked us in. The religious women took off of their petticoats to section off an area where buckets were. The train started to move. Even the little bit of window was wired up. We were squeezed in like sardines, we couldn’t move. One elderly lady woman became sick. People said, you may have to bear it in please. It was so quiet; people didn’t talk to each other. My mother looked at me; we didn’t know what was happening to us. We stopped at every border. We traveled for three days and three nights, only one time did they open the doors of the boxcar. I emptied the buckets of our boxcar. One German asked me if I had any diamonds that I should give to him.

And then we got to Auschwitz. We were thrown out of the boxcar like garbage. No one told us anything about what was going on. Then there was those shaven heads, those bald heads. When we arrived at Auschwitz, it was tumult, it was pandemonium, it was insanity! We got off the train and we saw all of these skeletons. And then we had to stand in line.

Religious Jews don’t show affection in public; you never see them holding hands walking down the street. My parents were religious people. I saw my father put his arm around my mother as they walked together. When they went the last way, they were together.

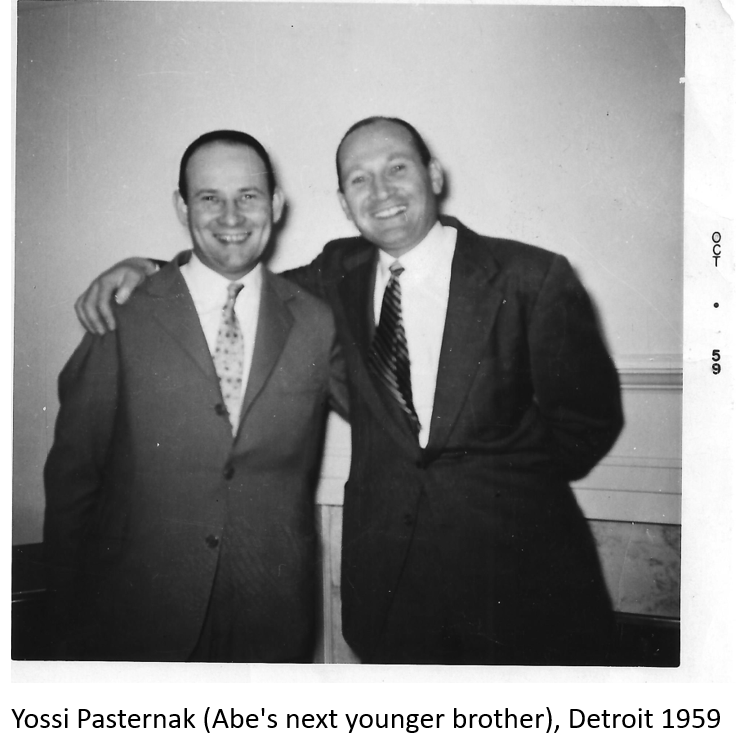

As I talk about it, I see the tumult of the people. In the tumult, I asked where is my kid brother, Solly. My brother Yossi said to him that he should go with our parents. I had to make one of the most horrible decisions about my kid brother.

“I told my little brother, I said to him, "Solly, geh zu tata and mommy." Go with my... And like a little kid, he followed, he did. Little did I know that, that I sent him to, to the crematorium. I am, I feel like I killed him! My brother who lives now in New York, he used to live in South America, every time we would see each other, he talks about it, and he says, "No, I am responsible, because I said that same thing to you, and it's been bothering me too." (Excerpt from Voice/Vision Holocaust Survivor Oral History Archive, http://holocaust.umd.umich.edu/interviews.php#pasternak)

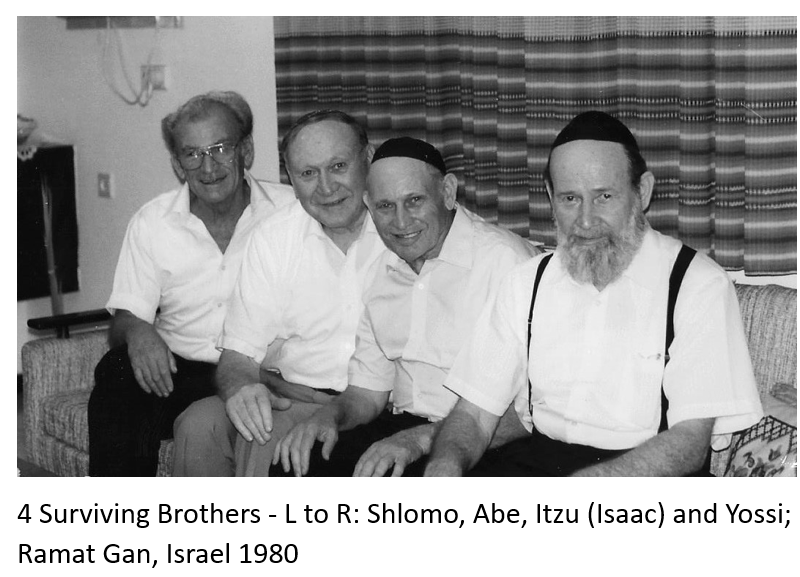

My brothers Yossi, Shlomo and I survived the Selection. My brothers Isaac and Mendel were drafted into the Hungarian labor force. I found out years later from a friend of mine who was with him that my brother Mendel died two days before the war ended.

After ten days at Auschwitz, the three of us were sent to Buchenwald. I did not get a number at Auschwitz; I just did not get a number. There, they gave us little bit more food than at Auschwitz. After a few days they shipped us to Geleine Zeitz. The moment we arrived, they put us to work. The Kapo gave me a big sledge hammer to knock down a brick wall that was damaged by Allied bombing. The bricks were red, there was a lot of red dust and dust got into my eyes. I said I can’t see and they put me in the infirmary. I was in the infirmary a few days and then they shipped me back to Buchenwald, just me, I was separated from my brothers.

Actually, I pretended to be blind and I was lucky. When I got to Buchenwald, I went to the infirmary. The doctor said open up your eyes, you can see, and good luck to you. It was a Jewish doctor. I was in Buchenwald for about three months. At Buchenwald we didn’t do much, we used to clean the outhouses, the camp.

Then we were sent to Schlieben. My job was to pour sulpher into a section of missiles. There was a chemist among us who told us that if we mix sulpher and sand together, then the missile would not reach its target, it wouldn’t have the full amount of sulpher in it.

The trigger of the missile was not entrusted to us, only to a German. But when the “superman” had to go to the bathroom once in a while too, we worked faster so that the trigger did not make it into the case. And when they got to the battlefield… So we did a little bit of sabotage. But we had to be careful, there someone always watching over us.

When we were traveling from Auschwitz to Buchenwald, we stopped at a railroad station in Dresden. There was a German soldier reading the newspaper which had big headlines. The guard asked him what the news was. He said, “The Allies have landed but we kicked them right back.” There was a guy standing next to me named Chaim who said to me, “Thank G-d, this is not going to last forever.” But it still took almost year before we were liberated.

The guards watched us to make sure we did the work. One time, there was a young kid like me, I was a kid too, who didn’t manage to do the work, maybe he was sick, I don’t know what, the guard hit him and hit him and hit him without Rachmunes, without any pity.

Many instances, we used to rush to garbage cans where they would throw away food that the SS or the Kapos didn’t eat, at one point a Kapo came out with a dog and said a dog doesn’t eat this. A guy said, I wish he would treat us like he treats his dog. That shows you the level we were treated.

In Buchenwald one time, a group from Czestochowa came, as I was marching to work, he yelled out in Yiddish, do you want a pair of Tephilin, (Jewish prayer phylacteries). I said throw it over the fence, I brought it into the barrack. I had to be very, very careful, if they found you davening, (saying prayers)… One Pole asked, “Why did G-d bring him here to see Jews.”

At twelve o’clock sharp, we had to go to outhouse, the outhouse had no roof. We saw a plane make a big circle and then he flew away. Then all hell broke loose, they bombed the factory at Buchenwald. They lined us all up with buckets of water. We were working together with the German Wehrmacht to put out the fires. Someone said, “Finally, the sun is shining in Buchenwald.”

After that I was sent to Schlieben, it was strictly Jews there, we were so full of lice. There were steam pipes there going through the barracks, we used to take our clothes off and wash them and wrap them around the steam pipes. We noticed how much lice there was but it didn’t last, you were soon full of lice again. The Germans were supposed to be so clean.

We used to see planes once in a while dropping leaflets, they came in like snow. There were maps which told us where soldiers were. That was help, at least we knew a little bit about what was going on. We didn’t hear any news; we lived in a vacuum, nothing.

After one day, the Germans said start getting ready. They loaded us up in boxcars, we traveled for ten days. We were lucky, we saw a lot of trains full of skeletons, we wondered if that were going to be us too. As we were traveling, planes were flying by, the train would stop. The guards used to run away. We went into the fields to find something to eat. I was lucky; there was a whole bunch of plum pits but it was surrounded by manure. I cleaned them up in the grass and cracked them up open and I ate them. It shows you the level of what these people did to us.

Then finally, finally, after nine or ten days, we arrived at Theresienstadt. They assigned us to various barracks and I was reunited with both of my brothers! We hugged each other and we cried. But they separated us into separate barracks. We were like strangers practically. We were waiting to be given different clothes.

At Theresienstadt, two German officers came in and we all stood up. They said to us please sit down. Hearing this from German officers was unbelievable. We wondered what’s going on because every time we saw a German officer we took off our hats and we saluted him. And then they gave us some clothes and a pair of shoes. It was better than what we had. Then all of a sudden, the gates were opened, and we heard screaming, we went out there. Soldiers started screaming, the war is over, the war is over, you are liberated. I got dressed and went out.

Germans were coming in one direction; I was walking with my friend in the other direction. My friend said to a German officer, hand me your boots and the officer did. I couldn’t believe it. I was more interested in getting a little piece of bread.

At liberation, I got so sick. I contracted typhus and I went down to 80 pounds. I must have eaten something because I was so hungry.

I recovered and went back home. I didn’t stay there long. Jews were leaving; I asked where they were going. Someone told me if you have any brains, pack up and leave because the Russians are not any better than the Germans. My younger brother Shlomo and my older brother Yossi were both sick. I went to Budapest to be with my uncle and aunt. Shlomo went to an ORT school (Jewish trade school), learned a profession and then went on to Israel. My brother Yossi also went first to Italy and then to Israel. He was on the Exodus (the ship that captured world sympathy when it was barred by the British from entering Israel). My brother Yossi later became a hero in the Israeli army.

From Budapest I went to Salzheim, Germany, DP (Displaced Persons) camp. I registered to go to the United States. I had a very famous cousin here, Joe Pasternak, the movie producer who sponsored me to come to the United States.

I went to Los Angeles for one month. I couldn’t take that life there. My cousin Joe bought me a ticket for Detroit where my uncle, my mother’s sister’s husband, Sam Friedman lived.

I came to the United States in 1947. In 1948, I was drafted. I entered the Army in 1949, I was discharged in 1950. I was recalled to active duty in 1950. I was twice in the Army. I received a certificate of achievement from General Clark. I was drafted because of the Russian blockade of Berlin. In June, 1950, Truman recalled all the Reserves for active duty. A psychologist talked to me and heard my accent. He found out that I was in a concentration camp and I served in Seattle as chaplain. I was discharged from the reserves in 1954.

I went to work for National Dry Goods and then I went into the tire business, I retired in 1994.