Ruth Adler Schnee

"Have compassion."

Name at birth

Ruth Adler

Date of birth

05/13/1923

Where were you born?

Where did you grow up?

Dusseldorf, Germany

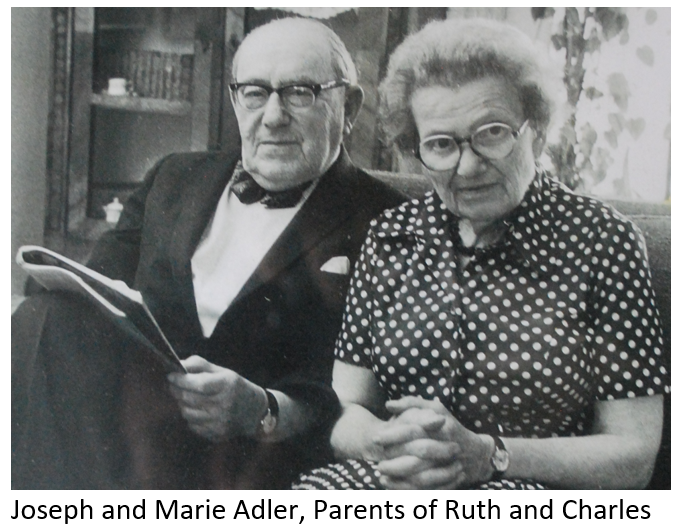

Name of father, occupation

Joseph Theo Adler,

Financial advisor and consultant

Maiden name of mother, occupation

Marie Florence Salomon,

Designer of books and book bindings

Immediate family (names, birth order)

Parents and two children: Ruth Adler Schnee and Karl (Charles) Heinz Adler (see photo)

How many in entire extended family?

Huge extended familiy

Who survived the Holocaust?

My parents, brother, and me

In 1927, when I was four years old, my family moved from Frankfurt to Dusseldorf. The Adler family traces its roots back to 1665 in Germany. We had the same business, book sellers and we lived in the same house in Frankfurt.

I think the reason that my father moved us to the more modern city of Dusseldorf was because his career grew; he was a very successful financial consultant. My parents’ circle of friends grew to include well-known painters and sculptors such as Kathe Kollwitz and others. They collected many of Kollwitz’s papers, drawings, and paintings.

Our life was very comfortable; dad had a fine position. Mother would go to Paris every season to buy my clothes. Later when we came to America, the only clothes I had when I started Cass Tech in Detroit, were couture dresses!

My dad’s business included later giving financial advice to Nazis.

In 1933, the Gestapo headquarters were across the street from us, I remember a big swastika that hung outside their headquarters. When the Nazis hung the banner, my mother said we have to leave Germany.

In 1923, she was in Munich during the attempted Nazi Beer Hall Putsch. The Munich Putsch was a failed revolution that happened when Hitler and other Nazis tried to seize power. She saw how fanatic the Nazis were.

My mother studied art at the Bauhaus at the time. The Bauhaus was a school that combined crafts and fine arts. It was known for the approach to design that it taught. In Weimer, Germany, she was in the Bauhaus school for applied arts.

Walter Gropius, the director, looked for creative people; he did not follow the old ways. But he did not want to accept women as he thought it would weaken the image of the school. My mother designed marbleized paper.

The painter Paul Klee was friends with my parents. They helped get him get a position in Dusseldorf. I played in his studio; my love for color and mobiles came from Klee. He would pay my dad with his paintings. He said here are my paintings, pick one, I cannot feed my children with my paintings.

My parents collected art and fine furniture.

Dad would not leave Germany. He thought that the country that gave the world Beethoven, Goethe, and Schelling would not go to a catastrophic happening.

In 1925, Mein Kampf was published. My father asked where are we going to go anyway. He had connections in Belgium and Holland but we stayed until the very end.

Politics, religion, and money were never discussed in our home. We never ate dinner with our parents. We were fed our meals with the staff. I had a nanny until the age of 16 when we left Germany.

I took dancing lessons to be socially accepted. In 1936, the Nuremberg Laws went into effect. My mother’s German staff was disbursed; Germans were no longer allowed to work for Jews.

We also could no longer go to school. In 1936, 1937, I went to Lausanne, Switzerland, my brother to England, to a boys’ school. I was very unhappy in Switzerland; I was so homesick for Dusseldorf. It was an all girls’ finishing school, many of the girls were very snobbish.

My mother knew we would eventually have to leave Germany.

We were a secular Jewish family. We never had a Seder at Passover, we did celebrate Chanukah.

In World War I, my dad was awarded the Iron Cross. He thought this would protect the family from the Nazis.

There was much going on to try to get Jewish money out of Germany away from the Nazis to Switzerland.

Being in the book business, we had many valuable first edition books. When the Nazi book burnings began, dad had his first edition books sent to Brussels. He was very dependent on selling a box of first edition books.

We were only allowed to take $4 out of Germany. Our dog was sent by air, we took the train to Aachen. We then took a boat to America.

We arranged for the box to be put on the train. The Nazis were searching people on the train. People were swallowing jewels. Dad threw the books out the window; we would have been shot if we were found with them.

On Kristallnacht, the Germans had IBM lists. My parents’ friends were all modernists. Hitler tried to show the German people that this art being created was insane, the art of Kandinsky, Picasso, and other modernists. Most were not Jewish.

There was a Nazi exhibition of German Expressionists called Entartende Kunst, (Degenerate Art). My parents were against us seeing it, the SS were there making a list of all those who attended it. I was dying to see it, finally my mother said okay. I wore a big felt hat so that no one would recognize me.

I loved Kandinsky’s work, that is where I developed a love for color. The Nazis came and destroyed everything.

On Kristallnacht, friends called to warn us that the Nazis were on their way to our apartment. All four of us left and walked through the streets. We saw people breaking into store windows, looting, throwing furniture through the windows. It was terrible.

We were afraid and decided to separate. My parents went one way, my brother and I another. We met Mrs. Pfaff, a neighbor, who took us to her apartment. Her husband was an architect. This was very brave of her; she risked her life to help us.

I was fifteen, my brother was twelve.

The concierge saw this and called the Gestapo to tell them that she was hiding Jewish children. The Gestapo called to tell her that they were on their way. My brother and I left.

Once in a while, relatives from England would visit us. My uncle insisted that we go to the synagogue. I didn’t know the way. He was furious. My brother and I walked past that synagogue and saw it being burned. The rabbi, Rabbi Klein, ran into the synagogue to try to save the Torah, he perished in the fire.

We went back to our apartment. When we came home, we saw that the door had been ripped off and the windows smashed. All of our furniture had been thrown out onto the street through the windows. The kitchen cabinets were torn off the walls. My mother’s Limoges china was smashed in a heap. My parents’ paintings were cut up in pieces.

When my parents came home, we sat and cried. We eventually started cleaning up; we slept on the floor that night.

One of our German neighbors, Frau Grutis, courageously came by to express her sympathy. She came with cookies and a pot of hot tea. I still have the pot. This was Friday night.

On Sunday, my dad was arrested. We had a little Dachshund. My dad took our dog out on a walk on Sunday. A Gestapo agent in plain clothes stopped him and asked if he was Herr Adler. The Gestapo told him to take the dog home and then to come with him. The Gestapo later brought my dad’s glasses, gold watch, cufflinks, and his ring back to the apartment. My mother was sure that they had shot him.

We found out later that dad was taken to a police prison. My dad told them that he had a court date on Monday, the next day, in Duisburg to represent a client who was a Nazi. So they came back to our apartment, such as it was, and picked up his things, his watch, glasses, and clothes. They took him by train to go to court to represent his client. They returned his clothes and things back to us.

My mother immediately became active trying to rescue my father. She tried to find relatives who could get us out of Germany. We would get calls everyday from England where my mother’s sister, husband, and their four children had left for in 1934 or 35.

My brother and I could leave on the Kindertransport that brought Jewish children out of Germany to England. My mother said absolutely not. She said we would either die together or live together but that we would never be split up.

She took us to Nazi headquarters because she wanted to know where dad was and what had happened to him. They wouldn’t give her any information, they wouldn’t let her get into any of the offices. They would take their guns and push us down the stairs. We would walk back up those high marble stairs. They never gave her any information but she never gave up. She went everyday, she threatened them that everything was so secretive.

One day, a Gestapo agent called saying that dad would be shipped to Dachau. She could come to the train station at a certain time and see him being put onto the transport. At 3 in the morning one night, she woke us up and we went down to the train station to say goodbye.

My mother kept working to get us out of Germany. She found family in New York who would give us a visa to come to America. She submitted this to the German government with the help of the Dutch and Belgian governments. She asked for my dad’s release from Dachau.

Then one day, my dad appeared in his black and white striped uniform. He was so weak, we barely recognized him. He was skin and bones. We were ecstatic to see him.

He came without his teeth, they whipped him, they had knocked out his teeth. He was starved. They pushed him out of the concentration camp. It was December, wintertime; he walked along the railroad tracks in his bare feet to Munich which was near Dachau. A soup kitchen had been set up by Polish Jews to feed and help prisoners. They gave him a coat and a train ticket to Dusseldorf.

My mother was working on the details for us to leave Germany. She tried to arrange for our furniture which she had repaired, our silver, and fine wines to be shipped from Germany to America. Our furniture later came, but it was shipped here without the sterling silver and the cartons of wine, they stole that.

It’s interesting that dad, until the day he died, had nothing good to say about Polish Jews. He was a Frankfurt Jew and felt more special.

There was a quota that Roosevelt had established. We had to go to Stuttgart which was the closest American embassy. We were examined physically and mentally.

We left Germany in February arriving in New York. I can’t begin to tell you how it felt seeing the Statue of Liberty, it was incredible! My parents were friends with Bruno Walter, the conductor, who stood next to me. We all broke down into tears.

We didn’t stay in New York, our cousin helped us get to Detroit. I have a diary that is housed at the Cranbrook Academy of Art archives in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan.

The first years here, dad couldn’t find a job for a long time. Mother never really adjusted to America.

There has been a film made about my life called, “The Radiant Sun.”

Synopsis of “The Radiant Sun” from the website of The Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation:

The Radiant Sun explores the life and work of mid-century American designer Ruth Adler Schnee, who has been called a “Detroit treasure” and an “American legacy.” Along with her family, Schnee fled Nazi Germany soon after Kristallnacht, and settled in Detroit. An internship with industrial designer Raymond Loewy and degrees from RISD and Cranbrook under Eliel Saarinen prepared her for a design career. With her husband Edward Schnee, she formed Adler-Schnee Associates, a design studio and store that helped bring modernism to Michigan. As a space planner, Adler-Schnee collaborated with noted architects including Yamasaki, Fuller, and Wright. The pivotal exhibition Design 1935–1965: What Modern Was (1991), featured Adler-Schnee’s textile designs. At age 90, she continues to work as a space planner and textile designer. The film, The Radiant Sun adds Adler-Schnee’s story to the growing scholarship on the American Modernist–era and expands knowledge about women designers’ influence on the built environment.

Dad wrote later wrote a book called, The Family of Joseph and Marie Adler: Jews in Germany, German Jews in America.

Dad lived to be 101. He had an enormous collection of Holocaust material which he donated to museums.

Where were you in hiding?

Fled from Germany to America

Occupation after the war

Textile designer, co-owner of Adler-Schnee design studio

When and where were you married?

May 23, 1948 in Detroit MIchigan

Spouse

Edward Schnee,

co-owner with her husband, Edward Schnee, Adler-Schnee Associates, design studio

Children

Three: Anita Deborah, Jeremy David, Daniel Joshua; all lawyers

Grandchildren

Six: Tona (m), Roderick, Sara Eliana, Jacob, Rebecca, Ariel, Dana

What do you think helped you to survive?

Our family fled from Germany to the United States. We really were a unit and also my art.

What message would you like to leave for future generations?

Have compassion.

Interviewer:

Charles Silow

Interview date:

11/26/2013

Experiences

Survivor's map