Martin Water

"Not to be complacent. Complacency can lead to upheavals. German Jews were too complacent."

Name at birth

Moishe Wasserman

Date of birth

10/08/1919

Where did you grow up?

Lodz, Poland

Name of father, occupation

Gershon,

Shoemaker

Maiden name of mother, occupation

Perla Devorah,

Homemaker

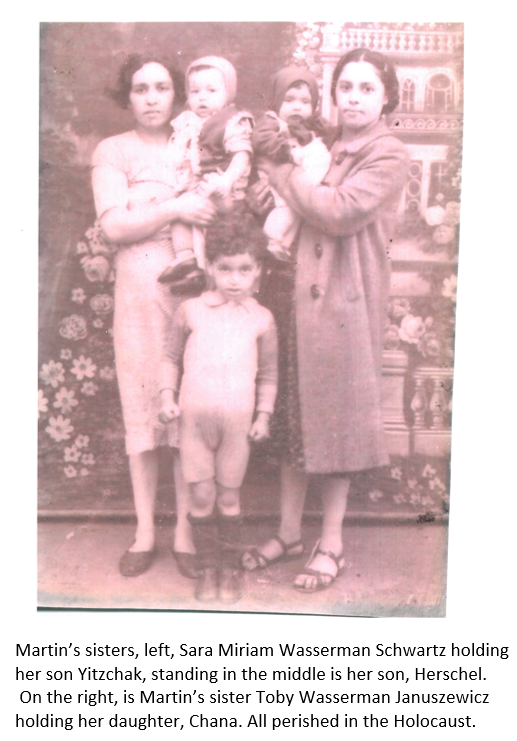

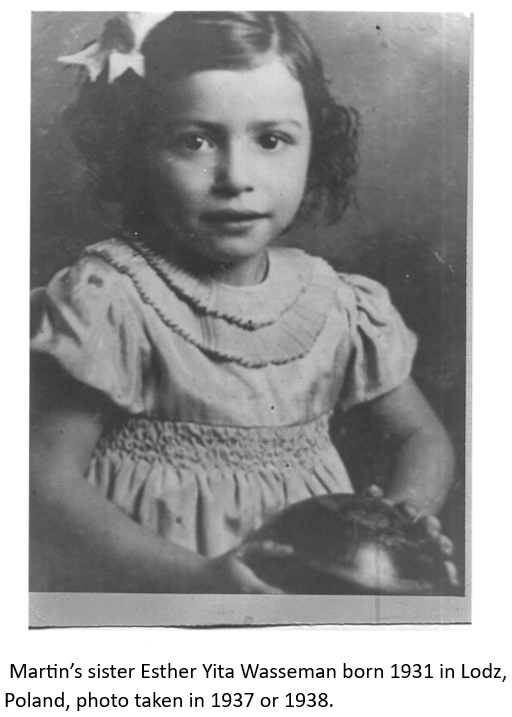

Immediate family (names, birth order)

Parents, Miriam, Toby, Hershel, me. Welwel (pronounced Velvet), Elijahu and Yita

How many in entire extended family?

Large family – I have no idea how many – included niece and nephew, brother-in-law Avrum. They were taken from the ghetto and never seen again.

Who survived the Holocaust?

My brother Welvel and me. Welvel now lives in Florida.

I was born in Lodz, Poland. In September, 1939 when the Germans invaded, we fled to Warsaw. There was so little to eat, so I went back alone to Lodz to find food. I couldn’t get back to Warsaw and was trapped in the Lodz Ghetto. I was living in Baluty, and working as a shoemaker.

For 4 ½ years, in Ghetto Lodz, I lived on a starvation diet, but for a short time, I received an extra portion of soup.

I was in charge of eleven ladies, I taught them to sew house shoes. In January, 1941, I was making straw shoes, so that the heroic German soldiers could march into Moscow and beyond.

I used a large needle to sew the braided straw. One day, I hurt myself and had a wound on my left hand. The wound got infected. I went to the clinic and a male nurse cut around the wound. He did not sterilize the scissors and my wound got worse. When I went back to the clinic the next day, he slammed the door in my face. The following day, I noticed two red streaks on my arm, so I went to the hospital. The doctor started to cut on my infected wound and saved my life. To this day, when the weather changes, it still hurts.

In July,1943, the SS men came and ordered all the people out of their apartments. I had a girlfriend who did not have a work permit, so she was taken away. I put my permit in my

pocket, and was also taken. We were put into a big wagon drawn by horses. On the wagon were two policemen. A lady begged them to let her go. She offered them money, but they refused.

I told my girlfriend to watch and listen to me. While the policemen were busy with this lady, I told my girlfriend to turn with her back to me. I put my hands on her waist and told her to jump. She did and they forgot about the lady. They grabbed me and told me that I will pay with my head. I wasn't worried. When the wagon came to disembark, the policeman let go of my wrist when I slapped him on the hand that he held me with. He let go and I jumped out. I ran to a fence, jumped over it, and came home.

As I stated earlier, I used to receive extra soup. One day, my coupon for the soup did not arrive, so I put away my tools and started to read a book. The officials came in and admonished me and told me that I could not strike. If I did not finish the house shoes, the ladies wouldn't have any lasts to sew. I was called to Mr. Izbicki's office. He didn't lift his head; he spoke to me in Polish and asked me why I didn't want to work. I told him why. He said that he is going to give me a kilo of potato peels. I told him that I'm not a goat but a man. So he got enraged. I have to describe his office. He sat behind a big desk, on top was a green felt. To his left was a telephone. To his right an inkwell. Meanwhile his wife Esther, a tall handsome woman lady, came in and told him that I was right. He said to her not to put her nose where it doesn't belong. I got mad and banged my wrist on the desk. The inkwell dumped out and spilled the ink all over the felt. I paled, so did he. He told me to get the hell out of his office. A few minutes later I got my soup.

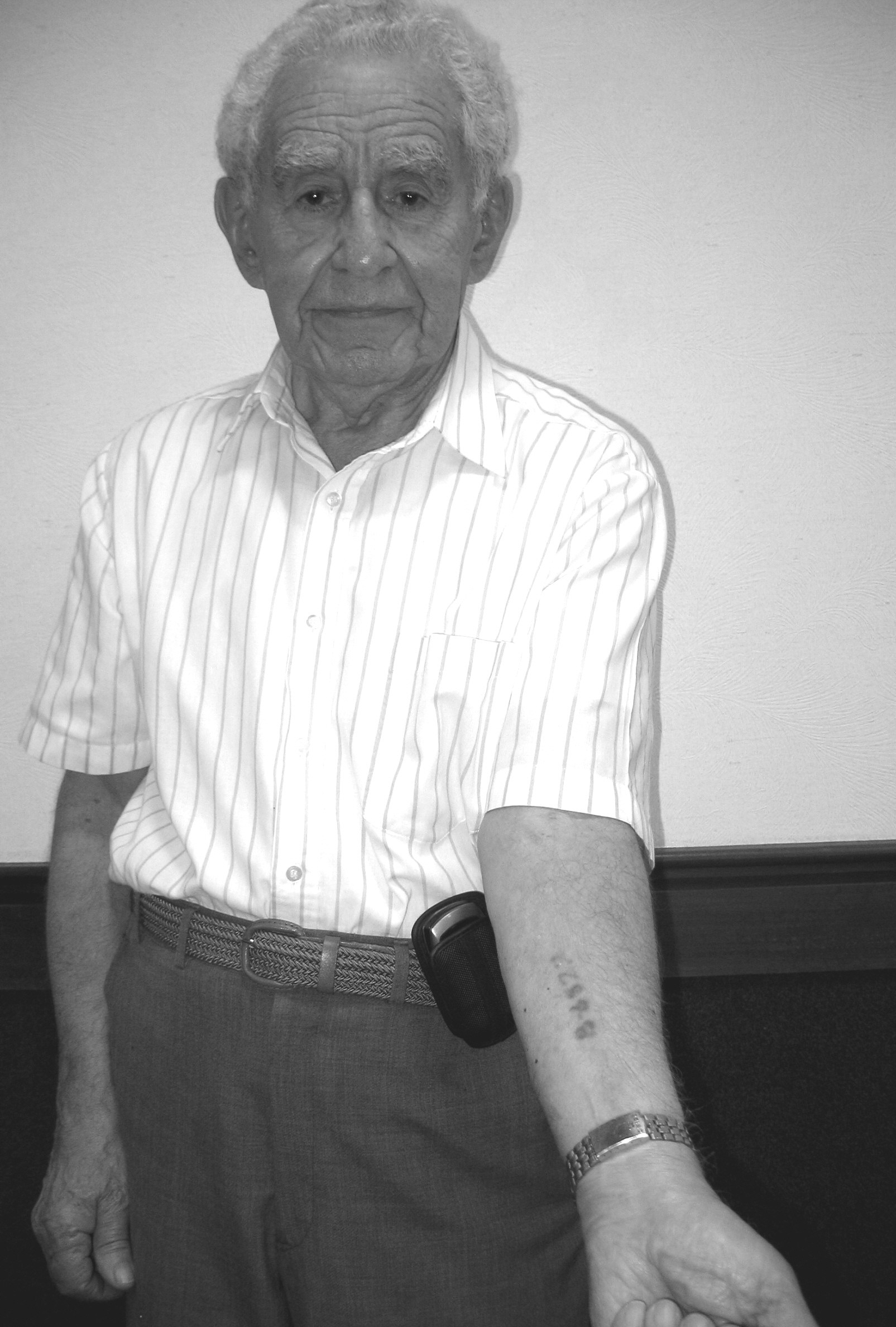

In August, 1944, I was taken by cattle car to Auschwitz-Birkenau. We couldn’t eat or drink for three days. After we traveled for three nights, we disembarked and saw three men with gas masks on. We found ourselves in front of Mengele who signaled me to the left. On the 15th of August, 1944, I was tattooed on my left wrist with the number B 6827. We were given gray striped clothes to wear and were taken to Gleiwitz concentration camp the next day.

One day in Gleiwitz, a haftling (an inmate) decided that he couldn’t take it anymore. He handed over his soup can to a young man. He went over to the SS men and told them to shoot him. The day was very cold and very windy. The SS man told the man to walk. While he was walking, the older SS man waddled over to the man, grabbed him by the neck and told him to go back to work.

A few minutes later, it started all over again. He went over to them and asked to be shot. Again they told him to walk, this time he wasn't stopped. The young SS man kneeled down and fired his rifle. He missed. The man turned around, opened his jacket, and gave him a target. The SS man fired again. This time he didn't miss. The man fell. The SS went over to him and shot a coup de gras, a bullet to his head.

The barracks we lived in had to be perfect, like in the army, and a tall boy in another bunk didn’t make his bed so it was wrinkled. When it was time for inspection, I told him I would take the blame for it. I was told to lie down and was beaten with a dolmecher (a rubber hose) ten times. I didn’t feel it. Bruno, the man in charge who liked me, was amazed. He asked me if I was related to the boy; was that why I had taken the punishment for him. When I said I wasn’t related, he was shocked. Afterwards, he started to give me extra food if it was available. After the war, I saw Bruno again in Lodz.

On December 23, 1944, there was a second selection in Gleiwitz. I was put on a pedestal between two big guys, like the slaves in the American South. My number was written down. On December 24, 25, 26, we did not go to work because of the Christmas holiday. There were at least four roll calls each day, and by December 27th my number still hadn’t been called, and not on the 28th either.

On the 28th, we were put on a truck to go to work. On the other end was my Kapo (guard), Bruno who was in charge of Block 2. He liked me and would speak to me in Polish and called me “Black Devil.” Bruno called me over and said that he had good news for me. The Kommandant had given him a radio to fix. He listened to stations from Paris and London about the progress of the war. The Germans made an announcement that due to a shortage of manpower, they were not going to dispose of people who could still pick up a shovel and a pick. That's how I survived the gas chamber.

On the 19th of January, 1945, as the Russians were advancing, we were marched by the Germans from Gleiwitz to Blechammer concentration camp. On the 23rd of January, 1945, the Germans fled Blechammer.

I organized a group of seven people, and we walked out of the camp. After walking about ten kilometers, we came to a clearing. I was the leader. I didn't know whether to go left or right. Before the war, I read books by James Fennimore Cooper who wrote about the Path Finder, Hawkeye. So I bent down in the snow and said, to the left.

A few minutes later, we met Russian soldiers camouflaged in white. A soldier pointed a gun at me. I told him in Russian that we were Jews out of a concentration camp. He told us to follow him to a farm. More soldiers came along. One soldier took out a gun. With his left hand he shot the farmer dead. He said the farmer collaborated with the Germans. He told the older lady there to cook for us, kluski and mleko (noodles with milk.) She understood that this was the best meal I had in five years.

At midnight, the guard changed and again I had to tell him that we were Jews out of a camp. In the morning, one man who was very sick and couldn't walk. I told the group that we can’t leave him behind. I found a sled and we started to go a little by little. The other people took off and I found myself alone with the sick man on the sled.

Now we traveled nine or ten days. I don’t remember where I slept or where we ate and how I took care of my companion. Then we came to the city of Czestochowa. I checked lists of survivors to find my uncle, but couldn’t find him. My brother survived in Russia

I left my companion at a camp there and in the morning, I took a train to Lodz. My first stop was to my uncle’s house on Wodna 26. I left; the inhabitants of my uncles’ house were now Christians. Then I went to the part of the city that used to be the Ghetto. I went to the apartment that I used to live in, same results. Then I met the Edelmans, a family who survived in the Ghetto. They told me where my neighbors now lived. I went there. Both families emigrated to Toronto, Canada.

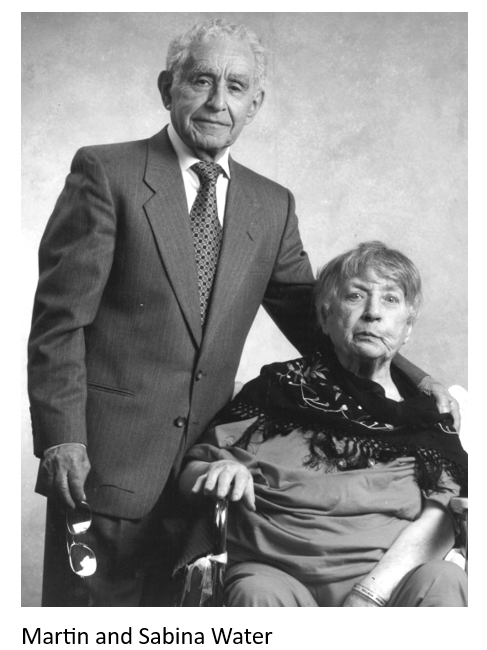

In May, I met my future wife there. She was living with her cousins in Lodz. One of them was in charge of food distribution. We fell in love and were married in November. We escaped to Germany so the People’s Army wouldn’t come and kill us.

We went to live in Neu-Freimann/Siedlung, a DP camp near Munich. I worked making shoes in the camp for three years. On March 23, 1948 we came to New York and then to Detroit. I went to work for Martin Rose, a friend. I later became an insurance man and retired from it after 24 years.

Name of Ghetto(s)

Name of Concentration / Labor Camp(s)

Where did you go after being liberated?

Bytom, Czestochowa, Lodz, Neu-Freimann/Siedlung, and then New York

When did you come to the United States?

March 23, 1948

Where did you settle?

Detroit, Michigan

Occupation after the war

Shoemaker and Insurance Man

When and where were you married?

November 18, 1945 in Lodz

Spouse

Sabina Chrapot,

Homemaker

Children

George (Gershon), limousine business Charlie, owner of karate studio in New York Pauline, paralegal

Grandchildren

Three grandchildren: Andrea, Jeremy, and Zachary Three great-grandchildren: Sophie, Avery and Magda Leah (Maggie)

What do you think helped you to survive?

Power of positive thinking. I don’t have a negative bone in my body.

What message would you like to leave for future generations?

Not to be complacent. Complacency can lead to upheavals. German Jews were too complacent.

Interviewer:

Charles Silow

Interview date:

02/16/2011

To learn more about this survivor, please visit:

The Zekelman Holocaust Center Oral History Collection

https://www.holocaustcenter.org/visit/library-archive/oral-history-department/water-martin-s/

https://www.holocaustcenter.org/visit/library-archive/oral-history-department/water-martin-s/

The Voice/Vision Holocaust Survivor Oral History Archive, University of Michigan

http://holocaust.umd.umich.edu/water/

http://holocaust.umd.umich.edu/water/

Experiences

Survivor's map