Irena Erlich

"To remember the lessons of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising and the great examples of heroism exhibited by the freedom fighters. We should not always go along with the status quo, but stand up for our rights. "

Name at birth

Rachela Fryzerman

Date of birth

05/01/1923

Where did you grow up?

Lodz, Poland

Name of father, occupation

Abram Fryzerman,

Medic

Maiden name of mother, occupation

Malka Leja (Liza) Gelberg,

Homemaker

Immediate family (names, birth order)

Parents, Paulina, Samuel (Moniek), Misza, Borys, myself and Zelman

How many in entire extended family?

Many

Who survived the Holocaust?

Paulina, Borys, and I

I was sixteen years old and getting ready to go back to school when the war broke out on September 1, 1939. Our home was very apolitical and we were unaware of what was happening inside Germany. German troops entered Lodz on September 8, shortly after invading Poland, and were welcomed with open arms by the large population of Volksdeutsche (German nationals) who lived there. The Germans immediately began seizing Jews for forced labor in preparation for the impending ghetto.

My parents, my brother Zelman and I lived on Aleja 1-go Maja Street no. 59 until our evacuation to the Lodz Ghetto in 1940. During the evacuation we were moved from a comfortable apartment with indoor plumbing to one room without any indoor facilities. There was a small metal heater in the room, but it was rarely used due to shortage of coal and wood. The roof was leaking, there was often ice on the walls, and our bedding was cold and damp. Eventually, the roof collapsed and we were forced to find other accommodations.

We moved to an abandoned, dirty room with a window facing a garbage dumpster where hungry rats unsuccessfully searched for food. The food rations we were receiving at the time were so small that food which was supposed to last eight days lasted only two to three days. The rest of the week we lived on soup that was provided at work. Since we did not have access to basic toiletries, we were dirty and infected with lice. I became ill with typhus and was taken to a hospital. I had to escape when I overheard rumors that the Germans were sending sick people to death camps. When I returned home, in order to improve my health, a doctor gave me two prescriptions for potato peels.

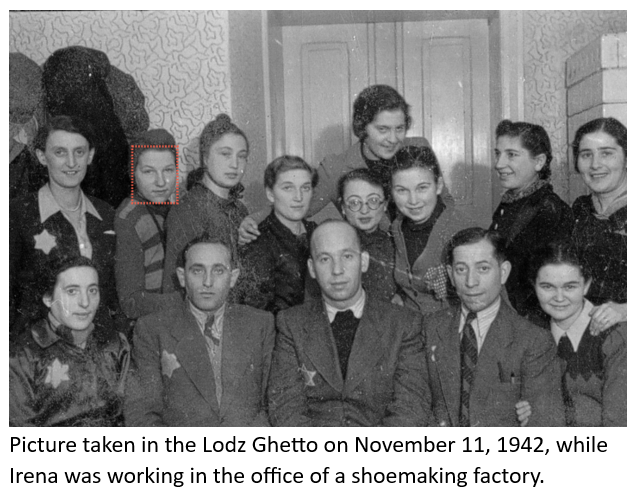

On April 30, 1940, the ghetto was completely sealed off and the conditions became even worse. I was able to attend school in the ghetto for a little while but when the school was closed, I was sent to work in a factory that manufactured wooden shoes. I was responsible for taking finished shoes from the factory to the warehouse. There were about one hundred of us working there.

We received a small ration of very watered-down soup each day. I remember a man who worked with me being so happy one day. When we asked him “why?” he told us that he found a small piece of potato in his soup. Everyone was always hungry.

Often on the way home from work, I was subjected to roundups organized by Hans Biebow, the Nazi head administrator of the Lodz Ghetto. At the sound of shots being fired into the air, everyone had to fall to the ground. Looking up was forbidden. During one of these roundups, I noticed my younger brother lying on the ground not far from me. I prayed that they would take me instead of him. Luckily, we both survived and went home without a word. The roundups often took place at night. Everyone had to get out of bed in a hurry and go outside. The Germans loaded people onto trucks and took them away.

Soon the streets of the ghetto began to fill up with people dying of hunger. People were lying dead in the streets and nobody paid attention. Hunger became so prevalent in the ghetto that often when someone in the family died, the dead body was hidden until that person’s food ration was collected by the surviving members of the family. Hunger forced people to act like animals.

There were accusations of stealing in the ghetto. When the accused was found out, he was hung in the main square and everyone was required to attend the hanging.

In August of 1944, as the Russian forces were getting closer to Wroclaw (Breslau), my parents, my brother and I were deported in cattle cars to Auschwitz-Birkenau. The cars were completely full, there was no room to sit down. Despite promises by Chaim Rumkowski, the chairman of the Jewish Council, that we were simply being relocated so that we could work and have a better life, the reality turned out to be quite different. On the walls of our wagon someone wrote in Yiddish in chalk, “Zug di Vidui” which means “Say your last prayers.” Apparently one of the prisoners from an earlier transport realized where he was when the doors opened and managed to scribble the warning.

When we arrived in Auschwitz, we were not permitted to take our belongings with us and were told that that we would have no need for them. Men were separated from women under the pretext of having to take a shower. That was the last time I saw my father and my brother. I was then separated from my mother who, after spending several years in the ghetto, did not appear strong enough to be able to work.

I was taken to the showers, shaved and forced to take off my clothes. I was given a rag to throw over my body as well as wooden clogs. Since all this happened toward the end of the war, we were not tattooed with our numbers. After the selection I was transported with a group of women to Peterswaldau (present day Pieszyce) camp which was a subcamp of Gross-Rosen. Peterswaldau was near Breslau (Wroclaw) in Lower Silesia.

Every morning we had to walk several miles to a nearby factory, manufacturing metal parts.

We lived in cold barracks and we were hungry all the time. We tried to pick up something to eat while going through the fields on the way to work. We risked being beaten if we were caught by the guards.

In the spring of 1945, we were called to a roll call in the middle of the night and were forced to march on foot for days without shoes, food, or water. As we later discovered, since the Russian forces were approaching, the Germans decided to move the factory and the machinery to a safer location. The orders were to kill all of us if the equipment did not reach its final destination.

Our death march ended in Chrastava (Kratzau), a sub camp of Gross-Rosen in Czechoslovakia. The guards in Kratzau beat us terribly. We were all bruised. On March 20, 1945, the notorious Dr. Mengele came for a visit. He asked the commandant what had happened to so many of us who were bruised. He was told that we were just clumsy and fell out of our bunks.

On May 9, 1945, Kratzau was liberated by the Russians. The next day after liberation, I contacted the police and the Red Cross and asked for permission to return to Lodz. The only means of transportation available to me was a train transporting coal. That did not stop me because I still had hope of finding my family.

When I arrived in Lodz, I found another family living in our house. Fortunately, because I had registered with the Jewish Agency after the war, my sister Paulina was able to find me. She helped me settle in Świdnica where several of our good friends lived. I worked in a store for a while and later became a director of a kindergarten. I met my husband there and we married in 1951. I also worked as a director of summer camps for Jewish children.

My sister Paulina and my brother Moniek were in Warsaw during the war, living on false identity papers. Moniek and his wife Sabina, heard about an attempt to rescue Jews by offering them passports and visas to Latin America. Because Jews who applied for these documents were allowed to wait their turn at the Hotel Polski, this operation was later named the Hotel Polski affair.

Unfortunately, the Hotel Polski affair turned out to be a trap set by the German authorities to find Jews who have gone into hiding. As a result, Moniek and Sabina were transported to Bergen-Belsen and later to Auschwitz where they were killed upon arrival.

In August, 1944, my younger brother Zelman was transferred from Auschwitz to Riese/Schotterwerk, a sub camp of Gross Rosen. He was forced to work in the mines. He was later transferred to an infirmary at Dornhau due to typhus and starvation. My brother died there two months before liberation at the age of 19.

My sister, Paulina, survived the occupation through her ingenuity and remained in Warsaw after the war. Boris survived the war in Russia. After the war, he came to live with me and my family in Świdnica and later followed us to Detroit.

Name of Ghetto(s)

Name of Concentration / Labor Camp(s)

Where did you go after being liberated?

Back to Lodz to look for my family

When did you come to the United States?

May 8,1969

Where did you settle?

Detroit, Michigan

How is it that you came to Michigan?

We had friends, Fajga Wancjer and Martin Wancjer, whose relatives Anna and Albert Fein were already there

Occupation after the war

Factory worker

When and where were you married?

1951 in Świdnica, Poland

Spouse

Szloma (Simon) Erlich,

Tailor

Children

Elizabeth, librarian and Mark, telecommunications

Grandchildren

Amy, Katie and Paul

What do you think helped you to survive?

The hope that I will see my family again.

What message would you like to leave for future generations?

To remember the lessons of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising and the great examples of heroism exhibited by the freedom fighters. We should not always go along with the status quo, but stand up for our rights.

Interviewer:

Biography given by Elizabeth Erlich, daughter of Irena Erlich

Interview date:

05/04/2016

Experiences

Survivor's map