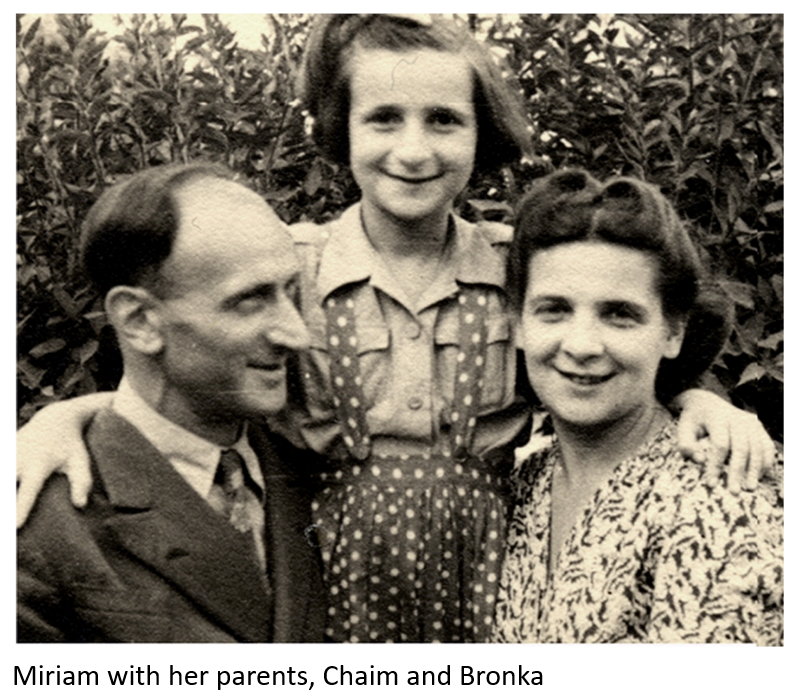

Miriam Brysk

"It is important to instill in others the understanding that the victims were not just emaciated skeletons but rather as people like you and I. They each had a life and a culture that, sadly, died with them. I plead for the continuation of the Yiddish language, as well as the literature, music, and art of that period. "

Name at birth

Mirjam Miasnik

Date of birth

03/10/1935

Where did you grow up?

Warsaw until I was 4 years old

Name of father, occupation

Dr. Chaim Miasnik,

Surgeon

Maiden name of mother, occupation

Bronka Zablocki,

Homemaker

Immediate family (names, birth order)

My parents and I

How many in entire extended family?

Grandparents (Ita and Avram Zablocki, Chana Liba Miasnik), aunts and uncles (Ala and David Wilner, Sevek Zablocki) and numerous cousins.

Who survived the Holocaust?

My parents and me, Uncle Sevek Zblocki; cousins Josei, Saba and Franka, Menachem Rozenbojm and those who left Poland before the war

I grew up in Warsaw until I was 4 years old. In 1939, after Nazi occupation, but prior to establishment of the Warsaw Ghetto, my parents and I left Warsaw and moved to Russian-occupied Lida, then Eastern Poland, now Belarus. We lived in the ghetto (1941-1942) and then hid in the forests of Belarus with the Russian Partisans till liberation.

My father, Dr. Chaim Miasnik, was a prominent surgeon in Warsaw. He was referred to as the “King of the Poor,” by the poor Jews whose lives he saved, who could not otherwise afford proper medical care.

In 1939, after Germany invaded Poland, but prior to the establishment of the Warsaw Ghetto, My parents and I escaped to Lida, Belarus, where my father worked as the head of surgery at the municipal hospital. In summer of 1941, the Nazis invaded Lida and established a ghetto. The Nazis ordered my father to operate on wounded German soldiers, while my mother worked in a leather factory run for the Germans. In the Lida Ghetto, I witnessed daily barbaric beatings of my fellow Jews.

On May 8, 1942, SS and their local collaborators raided the ghetto and forced all Jews from their homes. Those who could not walk were immediately shot to death in the streets. My family was marched from the city into the countryside. They heard gunfire in the distance. After a selection, my parents and I were sent to the right - toward death.

We were beaten with metal tubes and forced to run faster, we were then suddenly stopped by a nearby soldier. The Nazis had apparently realized that they still needed my father's surgical skills, and we were ordered to go back -toward life. Those sent to die, some 80 percent of the Lida Jews, watched as their children were thrown into a pit and blown up by grenades. The other Jews were forced to undress and then shot into a mass grave.

It was rumored in the ghetto that Russian Partisans were operating in the nearby forests. One night, two Jewish Partisans from the Lipiczany forest snuck into the Lida Ghetto to bring my father back with them (so that he could operate on wounded Russian partisans in the forest).

In the forest we were sheltered by enclosures dug in the earth called ziemlankes. The Partisans obtained their food supply by raiding nearby peasants, I was considered a danger to the Partisans (as I was a child of only 8, I might cry out and alert the enemy during Nazi raids on the forest). I was, in fact, the only Partisan child in the forest.

As my father was often away operating on stranded wounded partisans, my mother and I were at the mercy of the Partisans, especially when German forces infiltrated the forest trying to capture the Partisans. At those times the Partisans threatened to kill us, if we tried to follow the armed men.

Sometimes, they abandoned us in the middle of the night, leaving us isolated. In particular, I recall a time when I became separated from my mother and I feared I would die freezing to death without ever seeing my family again. In all of these circumstances, I endured unbearable cold and hunger for days at a time, with only trees for shelter and snow for hydration and food.

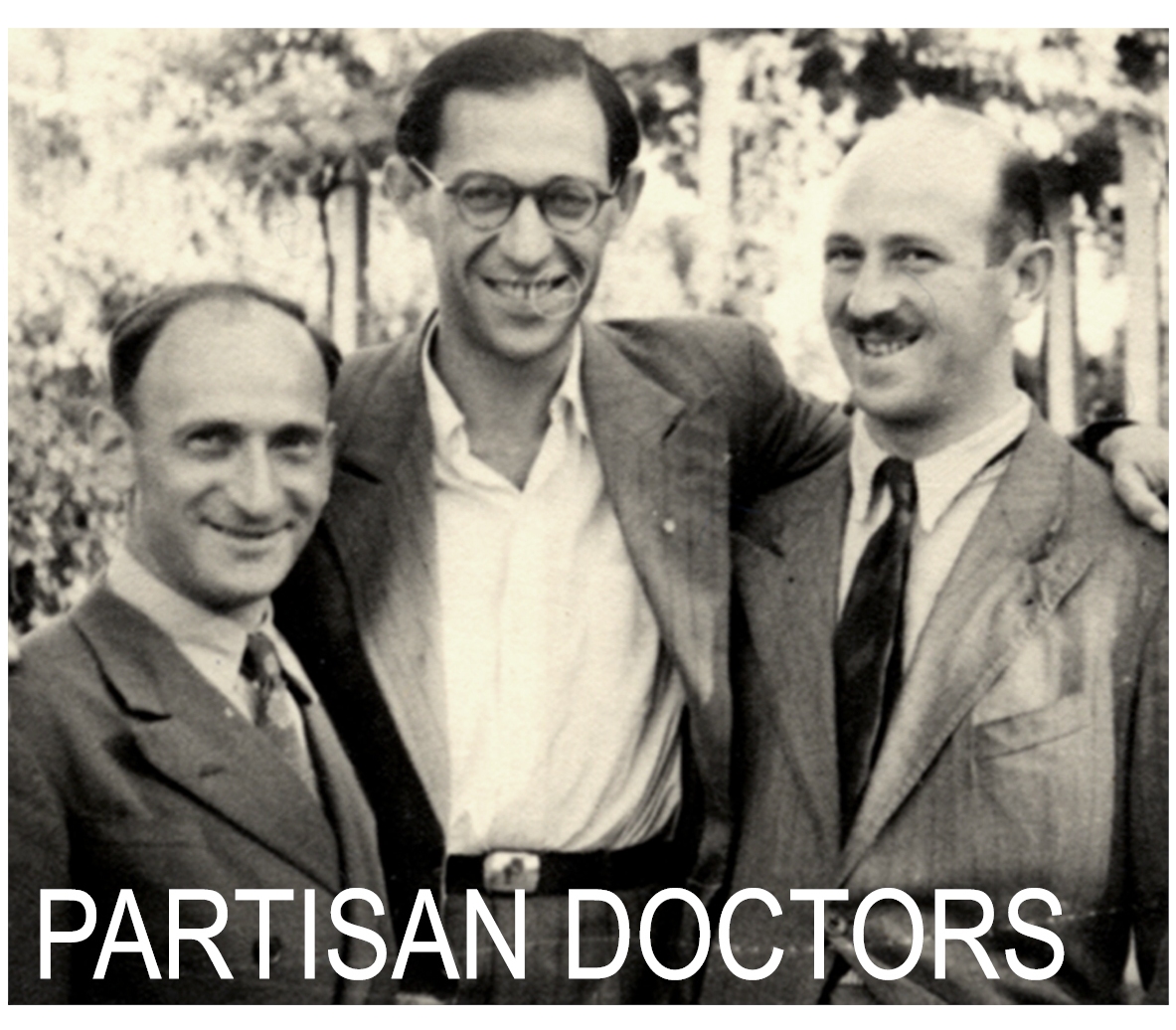

There was only so much that one doctor could do to save wounded Partisans. In response, in early 1943, the Soviet Partisan high command ordered that a forest hospital be established on a small remote forest island surrounded by swamps. My father, Dr. Miasnik, became its chief of staff and he recruited Jewish doctors and nurses who had been rescued from the ghettos. He also recruited other helpless Jews who were not Partisans to be part of the hospital staff, saving them from the dangers of life as unarmed Jews in the forest.

The hospital staff built ziemlankes for shelter and raided nearby hospitals for medical supplies. My father saved hundreds of lives in the forest. He secretly left the hospital to operate on unarmed forest Jews who were not allowed into the Partisans. He also protected many Jewish partisan women who were threatened with eviction in anti-Semitic attacks on Jews.

To protect me, my father shaved off my hair and my mother sewed boy's clothing for me to wear, then my father gave me a pistol of my own. After liberation in the summer of 1944, my father was awarded the “Order of Lenin” (a Russian Honor) by the Soviets in Moscow.

Disillusioned with life under Communism, my family escaped from Belarus and we traveled as refugees through most of Central Europe, sometimes crossing borders by foot, to finally reach an Allied-occupied country-Italy. My father was allowed to operate on Holocaust Jews in Rome, as these survivors refused to be treated by Italian doctors. My family immigrated to the United States in 1947, when I was 12 years old.

Where were you if you were in hiding?

In the summer of 1942, in response to a rumor that all Jewish children in the ghetto would be executed, my father snuck me into the infectious ward of the hospital. After that, I was hidden for a few weeks on a farm of a peasant woman whose little daughter my father had saved. Then I returned to the ghetto when the rumor proved false.

Where did you go after being liberated?

Immediately after liberation, we were sent to Szczuczyn, a small town in Belarus where my father ran a hospital run by the Soviets. Later, we escaped to Central Poland. From there, we travelled as refugees through Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Austria and Italy.

When did you come to the United States?

In February 1947, we immigrated to the United States and settled in Brighton Beach in Brooklyn, New York. For the first time, I began attending a regular school and slowly, but not easily, I became Americanized. I attended New York University for my BS.

Name of Ghetto(s)

Where were you in hiding?

Forests of Belarus

Where did you go after being liberated?

Immediately after liberation, we were sent to Szczuczyn, a small town in Belarus where my father ran a hospital run by the Soviets. Later, we escaped to Central Poland. From there, we travelled as refugees through Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Austria and Italy.

When did you come to the United States?

In February 1947, we immigrated to the United States and settled in Brighton Beach in Brooklyn, New York. For the first time, I began attending a regular school and slowly, but not easily, I became Americanized. I attended New York University for my BS.

How is it that you came to Michigan?

We moved to Ann Arbor when my husband (a physicist) took a job at the University of Michigan.

Occupation after the war

Biochemist, Professor, Artist

Spouse

Henry Brysk,

Physicist

Children

Judith Brysk, M.D.; gynaecologist in Birmingham, MI Havi Mandell, MSW, PhD; psychologist in Las Vegas, NV.

Grandchildren

Five: twins - Benjamin and Joshua Rocher, Hannah Graff, David Mandell, and Sarah Mandell.

What do you think helped you to survive?

My father’s competence as a surgeon, and the need for his services during the war; and the rest were “accidents”. There were so many times when we came close to death. It’s a mystery to me why so many others died, yet we survived.

What message would you like to leave for future generations?

It is important to instill in others the understanding that the victims were not just emaciated skeletons but rather as people like you and I. They each had a life and a culture that, sadly, died with them. I plead for the continuation of the Yiddish language, as well as the literature, music, and art of that period.

Interviewer:

Charles Silow

Interview date:

08/05/2011

To learn more about this survivor, please visit:

The Voice/Vision Holocaust Survivor Oral History Archive, University of Michigan

https://holocaust.umd.umich.edu/brysk/

https://holocaust.umd.umich.edu/brysk/

The Zekelman Holocaust Center Oral History Collection

https://5152.sydneyplus.com/argus/final/Portal/Default.aspx?component=AAFG&record=d2292fee-3276-432b-b6bc-a990b06123d5

https://5152.sydneyplus.com/argus/final/Portal/Default.aspx?component=AAFG&record=d2292fee-3276-432b-b6bc-a990b06123d5

Experiences

Survivor's map