I remember my dad standing in a field with 100’s of other people, it was cold and raining, I was holding onto my father’s hair. My dad reassured me that everything would be all right. We were in a line. I was scared. People were falling down. I later read about the counting at Theresienstadt, it described how everyone lined up, everyone started counting. The count got messed up, and the Germans started over again. When I read that, I had goose bumps. I remember it was freezing cold; we were out there from 7 AM till midnight. 100’s of people died right on that spot, the sick and the elderly, I was holding on to my dad’s hair for life.

Another memory that has been with me since I was 4 ½ or 5 years old. There was a little grassy hill, where I used to play. Across from it was a building sitting on a hill. I sat on the hill a lot, there were dandelions there. At some point, I remember seeing wagons pulling up to this building. I became conscious of the fact that the wagons were holding dead bodies. There were funeral and regular wagons. I would watch the wagons bring bodies there. I connected their death to Theresienstadt. I didn’t know any other way of living, I didn’t know people lived differently.

I remember when we first arrived at Theresienstadt, we were taken to the barracks, my mother was terrified.

I absorbed the emotions of those around me. I remember being bitten by a bee on my lip. I really hurt. There were 100’s of people. I was shoved into a cavernous room, it was traumatic. The bee sting really hurt.

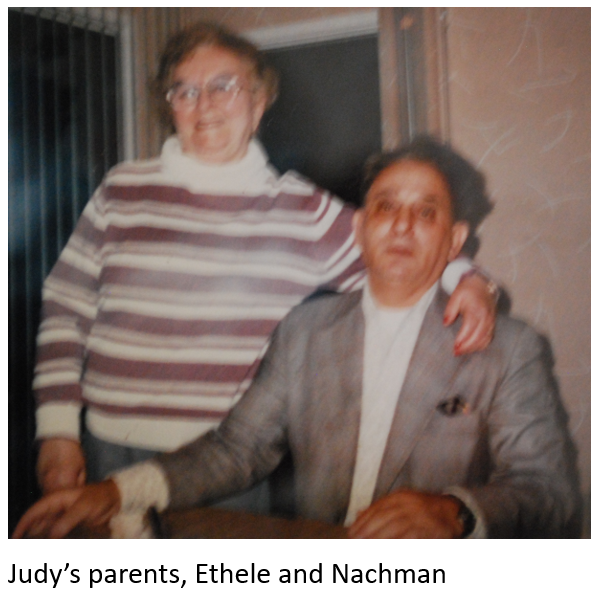

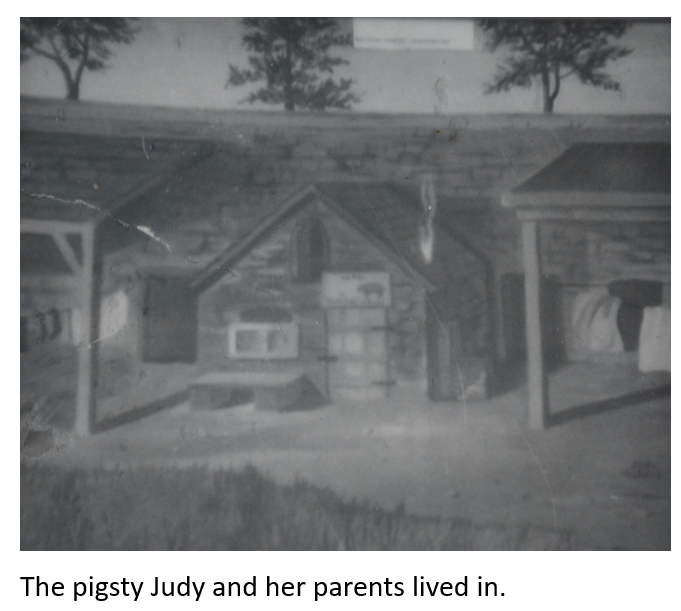

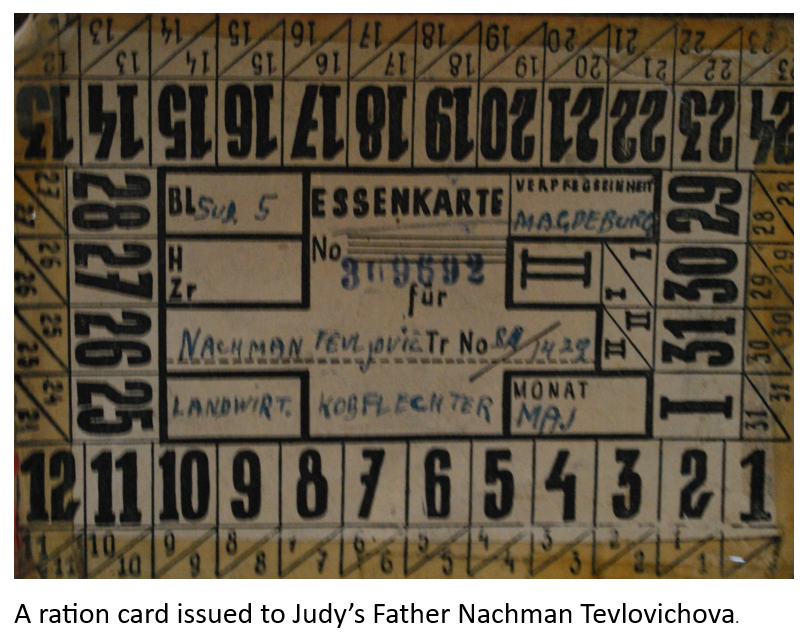

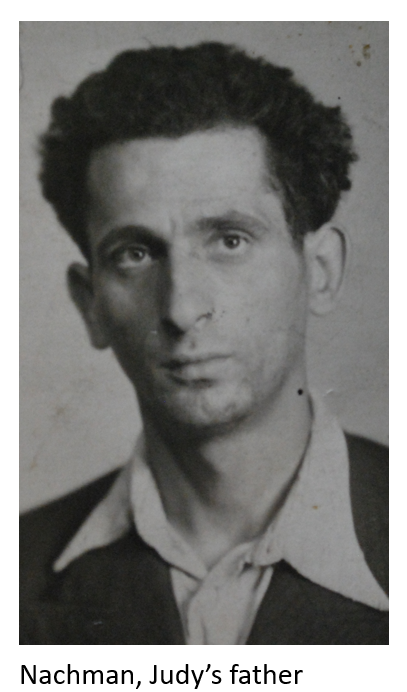

We were separated originally, I remember being with my mom. My dad became valuable to the Germans. He made a basket to catch fish. This was important to the Germans because they could have access to fresh fish. As a reward, my mother, father and me moved into a courtyard that had what was once a pigsty. We lived under a brick wall. Above the brick wall were orchards with fruit trees. They gave my dad the pigsty for us to live in. My dad called it the Golden Pig Hotel. It was the size of about two small bathrooms put together.

I have a memory of my dad climbing up the walls of Terezin with a rope tied around his middle to steal fruit from the orchard above where we lived. My job was to yank the rope in case anyone came. He was very capable when we were in the camp. Because of him, mother and I survived.

Before we were taken to Theresienstadt, I remember when we were living in Prague, there was a lot of anxiety in the house. My mother was crying. It was after Shabbos (the Jewish Sabbath) had started. Something occurred. We had to leave and I had to have a yellow star on my coat. We took a train to Theresienstadt, this was in 1941.

We schlepped (carried) our bags and stuff with us. One of their neighbors offered to keep me; I thought this was a frightening experience,

I remember being in a barracks, with all women. I have these vague kinds of memories. One was that there was no soap or a lack of soap. My mom very upset. The house on the little hill turned out to be a crematorium. That traumatized me, before I had no awareness of death. At the age of three, that caused me a lot of anxiety. I felt like I had been somehow destroyed, being raised up with anxiety.

The first time I went to sleep away camp, Fresh Air Camp it was called in Detroit. There were eleven in the cabins. At night, I became petrified, I was away from my parents, I felt such anxiety. I couldn’t sleep in the cots. They allowed me to sleep in front of the bathroom where there was light.

In the 5th grade, we lived on Charlevoix Street in Detroit, I ran home after 3:30 PM, in anticipation of the night coming. Fear overwhelmed me; I couldn’t articulate what the fear was about. I lacked the ability to articulate it. I had episodes of intense, overwhelming anxiety and fear, Theresienstadt “knocked me out” big time.

I absorbed my parents’ fear. I had an enormous fear of losing my father. I thought he was keeping us alive. My remaining alive depended on him staying alive. When I was 5 ½, near end of the war, there were increased transports being sent out to Auschwitz. My dad’s name was put on a transport to leave. I have two intense memories from that, my dad being on a train and the feeling that I think we were going to die.

There was a wooden depot; there were two sentry booths with Nazis on each side who had guns. Dad when he could get, still talking to us, yelling to us, I didn’t know that that train was taking these people to die at Auschwitz. My mother did not explain it to me; I just remember this severe, intense anxiety. And then eventually, the train pulled out with my dad.

My mother said we have to go back. I told my mother no, because daddy’s gonna come back and I have to wait here, in so many words. I refused to leave from where the train had left.

And little by little the people that were there to wave or to say goodbye to whomever was on the train, everybody left. My mother got mad at me and gave me a whack because I refused to leave. I told my mother, but daddy’s going to come back.

The train station was not that far from where we lived, it was near that courtyard. All I remember is that eventually my mother yelling at me, everybody was gone, she left me there, she told me, come home when you come home.

She simply left me there. I was very single minded because I remember saying over and over, they’re going to bring daddy back.

A truck, about an hour after the train left or something like that, I don’t know the exact time, was sent out to stop the train. The truck had in it the Nazi guy that my dad built these fish catching things for, and that my dad apparently was of use to this guy. When he found out that my dad was on the train he sent the truck out…

to get my dad.

The part that I myself remember is still being at the train station where the train pulled out on this wooden, plank that was set up there. And I remember a truck with my father sitting in the bed of the truck, coming back to Theresienstadt with my father. And then I went home. It seems unlikely and unreal but I remember it. He did come back.

I was three and then four, and then five. I don’t have any memories of being with other children, I don’t know how old you had to be. I did not attend any kind of formal anything. I remember going to school right after we were free in Prague.

I remember being with adults. I remember people that would disappear; they were people that my parents apparently must have had some kind of relationship with.

I have one clear memory of going to see this couple with my parents in Terezin to where they lived. I remember them asking me if I wanted something. I said I wanted bread with some jam.

The woman actually gave me some kind of piece of bread with something like jam, because it was sweet. I remember them laughing, my parents laughing and I was embarrassed. I remember feeling ashamed that I asked for bread, maybe because I should have understood that.

Mainly I remember my mother and my father and being by myself a lot. My father went to work of some sort.

I think he was in a group that used to like field work and then he caught fish for them.

My mother, I do not have anywhere near as clear memory of mother as I do of my dad during that time.

I think my dad played a far more prominent role than my mother did, but she was there.

What I remember about my mother is always trying to give me something to eat and me not wanting to eat.

One of the memories that I have, in terms of food, I have never in my adult life or in my young childhood or ever been able to drink milk. In my mind, I trace that back to the fact that one of the things my dad for this Nazi guy is he and his wife had a cat. One of my dad’s jobs was to bring goat milk to the cat, so that the cat would be fed. He would steal some of this milk and put it into something or other, I don’t know how he did it, and bring this milk back to this, where we lived in this pigsty. It had like a skin and stuff on top and it, it grossed me out even then. I was a little kid, but I didn’t want to drink it but I was forced to drink it.

I’ve never been able to drink milk and don’t have even the remotest desire to taste it.

Right before the end of the war they brought a transport into Theresien from some other terrible camp where these people had been. They brought them in these cattle cars. Many of them were unable to walk and they were on stretchers, what to me looked like stretchers, I thought. They were lying down and I remember going with my dad that same train station where they were being unloaded into Theresien. And my dad had in his pocket a number of cubes of sugar. I remember holding his hand and he was walking around where the people were taken off the train, the ones that were really sick.

They were lying on the ground, I thought on stretchers but maybe it was just the ground. My dad gave one of them a little sugar square. When the person that was lying there they put their hand together like in a prayer motion and were begging my dad for sugar. My dad had a few more pieces like that and he gave them to these people until he didn’t have anymore, he didn’t have that much. I remember thinking that these are like really, really sick looking people and something’s wrong with them.

I have those kinds of memories. I have memories of sitting on that hill where I used to sit and at various times airplanes would fly over and they would drop silver threads of some kind of papers, silver paper. I don’t know what that was; I never read about it, I never had my parents explain to it.

But at some point, and I remember scurrying around, around that hill to pick up these silver little things that came off the planes flying down, it was like a wonderful toy to me.

It was something I could collect that, that was gorgeous, that was on the one hand but then on the other hand if I looked across the street there might be another wagon pulling up with dead bodies. And I think at some point I was cognizant of the fact that this was some place that dead bodies were brought.

They burned them in the crematorium. As a matter of fact, at the end of the war they, many people were dying faster because there was more sickness, they weren’t being taken care of at all.

They were burning them fast. One of the jobs my dad told me he had was to do, with others, was to carry ashes from the crematorium over to a river and dump them into the river. My dad collected some of these ashes and put them in some kind of a leather thing. Sometime in the seventies, he and my mother went to Israel and he had it buried there at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem.

He kept those ashes, and I remember those ashes terrifying me throughout my childhood after the war because I knew they existed. I understood what they were from.

Here’s what I remember about liberation. I remember my parents fighting and the reason that I remember them fighting was because everybody, I didn’t understand at that time, but apparently everybody around us was getting sick. I think an epidemic of typhus broke out, which I did not understand then. My father got a hold of some kind of a little wagon and a horse. He wanted to get out of there immediately and go back to Prague. I knew that Russian soldiers had come in. I remember one of them rolling up his sleeve and showing me all these watches he had. He had like three or four watches on his hands, he was collecting, I don’t know where they were getting them, but they were taking watches.

I remember my dad and mother fighting and my mother wanted to say goodbye to certain people, and my dad was rushing her. Hurry up, hurry up, we have to leave, we have to leave. The next thing I remember is being in that little wagon, it was some kind of a little farm little wagon.

We were riding back to Prague and I remember dead horses along the side of the, the road. I just remember, like flash memories of looking, there was a dead horse and then I saw another dead horse and that scared me.

Seeing all of those human corpses, I remember being fearful about dying all of my life, from early childhood on. I remember fearing that my mother would die, fearing that my father would die, having this vague fear about people disappearing, like somebody would be there and then not be there. I think it handicapped my ability to make close connections throughout a lot of my adult life later on.

But as a child, I had a fear that was at times overwhelming. I didn’t have a name for it. I don’t think that my parents even understood that I had it.

My dad had some kind of a nervous breakdown when we lived on the east side when I was about eleven.

I did not want to be separated from my parents and I was always fearful that they were going to die. But then it became a generalized fear that I was afraid that people were going to die, or that I was going to die. As I got older I began, you know, reading and explaining some of it to myself.

But by then it was like some of that fear became real because, I think, my dad started becoming basically non-functional. He never had a steady job. I think he came out of there broken.

I was growing up in the United States as an American kid. I learned how to speak when we moved to Louisville. I spoke perfect English, like within three months because I was eight and a half, nine and they put me in kindergarten, I was so humiliated. They did not have English for foreign born then.

I taught myself how to speak and the more that I acclimated in the U.S. as part of my kid life, the more I began to see how not acclimated my parents were.