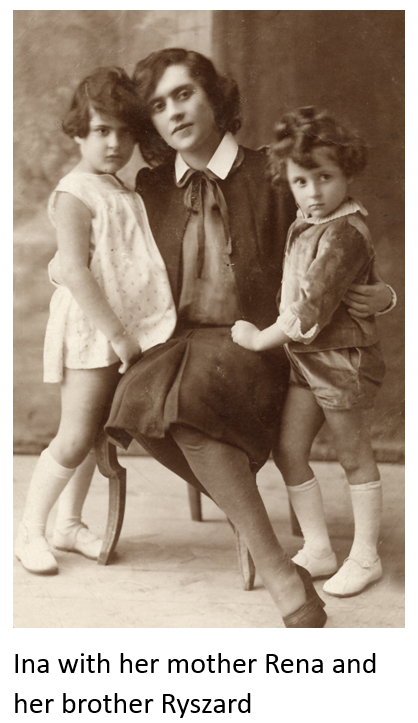

I was born in Warsaw, Poland in 1937 shortly before the beginning of the war. My father owned and operated a lace factory. The family business was very successful, enabling the family to live a life of relative luxury. My mother traveled frequently throughout Europe with my grandfather, while a loving nanny cared for me and my brother. My father, in the meantime, ran the factory. Due to the nature of his business, my father had established relationships with a Nazi officer.

With the establishment of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1940, and the edict prohibiting gentiles from working for Jews, my nanny was forced to leave our home. Control of the lace factory, which was located on the border of the Warsaw Ghetto, was assumed by an SS official named Bernard Hallman, who converted the factory into a repair facility for German uniforms. Hallman, with whom my father had prior business and social ties, was a compassionate man. I referred to him as our “Schindler.” He allowed my father to continue running the factory under his supervision, allowed our family to remain in our home, allowed my mother to work as a “lunch-lady” at the factory. In exchange for his protection, our family surrendered money, jewelry, furs, silverware and other valuable items to Hallman and his wife.

In April 1943, Hallman warned our family of the impending liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto. Hallman arranged for our transportation out of the Ghetto. (Their new name was “Bogacki”.) I remember my mother sewing her diamonds into the hems and buttons of her dresses to use as currency in exchange for future protection.

Following our escape from the Ghetto, our lives became very difficult. We were hungry (those hiding us could not obtain extra food without arousing suspicion that they were harboring Jews), we were required to remain quiet all day, and had to “schedule” our trips to the bathroom. Given my Jewish appearance and childish demeanor, I was usually confined within the walls of our hiding spots. My mother, however, could “pass” as a gentile with her Aryan looks and cultured sophistication. On occasion, she ventured outside to find food for our family and obtain information about their situation.

In August or September 1944, my family and I took refuge in the apartment of a Polish engineer on the outskirts of Warsaw. For several weeks, there was talk of a Polish underground uprising in Warsaw, which we hoped would result in the Russian soldiers coming to our aid. Instead, Nazi soldiers invaded our building. My father and brother hid in an attic, but were ultimately captured. I never saw them again and, to the best of my knowledge, my brother and father were shot by the Nazis shortly after the raid.

My mother and I were rounded up with other Polish tenants in the building and taken to a nearby walled field. Hundreds of Poles (hidden Jews and gentiles alike) were held there for a week to ten days and subjected to horrifying conditions. There was no food, shelter, or water, and Nazi soldiers with machine guns regularly took “target practice” at random prisoners. My mother was resourceful. On occasion, she was able to pick some potatoes and secure water for us.

During our time in the field, we never discussed the probable deaths of my father and brother. There was not a lot of conversation, it was just understood. I felt much protected from direct information. I didn’t want to ask and my mom didn’t want to tell. We focused on surviving one day at a time.

Eventually, the Nazis placed their Polish prisoners on a train, most likely headed for a concentration camp. As the train slowed down in a small Polish village, some onlookers yelled to them, “Jump off the train and we will help you.” My mother and I, with approximately thirty other Poles did just that. Several were immediately shot and killed by Nazi soldiers, but most escaped safely and were led by the compassionate villagers to a nearby gymnasium where we hid overnight. When she awoke the next morning, my mother’s shoes had been stolen.

My mother obtained information that the sister of the Polish engineer who had hidden them last lived in a remote area near the gymnasium. The next day, we walked to this woman’s home and were given refuge. I was only 5 years old at the time and cannot recall the woman’s name or the specific location of her home. However, I remember feeling “frightened” by the woman’s appearance and demeanor. She was an elderly piano teacher with horrible sores on her legs and a devout Catholic. In exchange for hiding us, the woman sought my conversion to Catholicism. I remember praying the rosary for hours.

There was one specific incident that exemplifies the woman’s righteous, compassionate nature. One day, Nazi soldiers knocked on the woman’s door, demanding to search her home for hidden Jews. The woman “stuffed” my mother and I into a closet and, just as the soldiers prepared to open the closet door, she unwrapped the bandages around her diseased legs -- exposing multiple, grotesque sores – distracting the men from further investigation. This righteous gentile woman harbored us for at least six months, until Russian tanks moved in and liberated us in the summer of 1945.

Following liberation, my mother went back to Warsaw to search for surviving family members, while I stayed on with the elderly Polish woman. My mother reunited with her cousins, the Kopers, and discovered that her brother, Abe Mussman, was also alive, because he was conducting business in the United States just before the war. Abe’s wife, Franka, and their two children, Bronek and Nina, however, remained in Warsaw during that time and were eventually captured and killed by the Nazis.

My mother and I returned to Warsaw for a short time. We resided in a bombed apartment previously owned by a Jewish friend who did not survive the Holocaust, but whose housekeeper currently lived on the premises. After reuniting with Uncle Abe, we moved to Sweden in 1946 and immigrated to the United States in 1949.

I attended high school and then college at the University of Cincinnati, where I obtained a degree in Art Education. I met my husband, Allen Silbergleit, while he was a medical student at the University of Cincinnati. We moved to Detroit in 1962, where my husband worked at Wayne State University and opened medical practices at St. Joseph’s and Crittenden Hospitals.