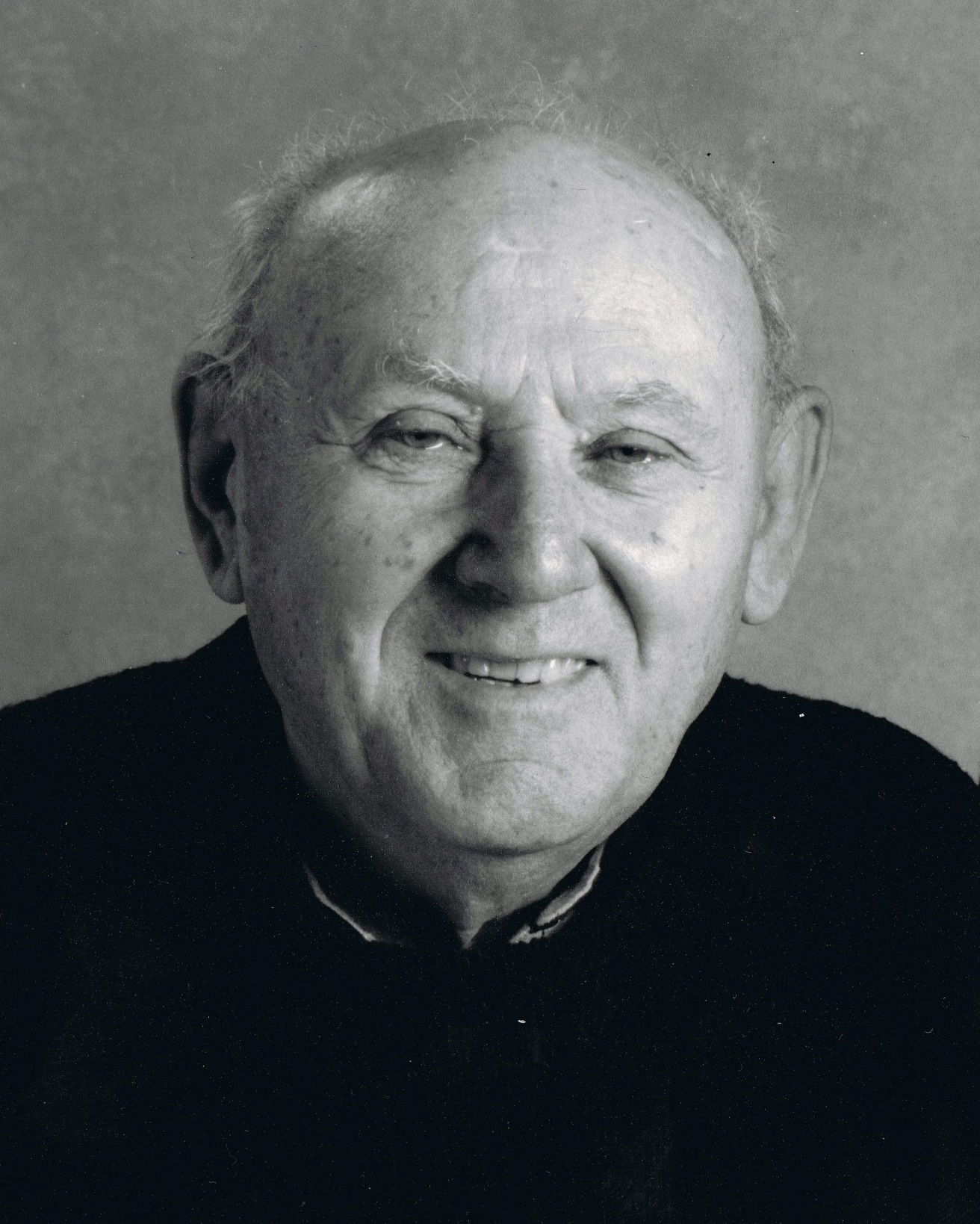

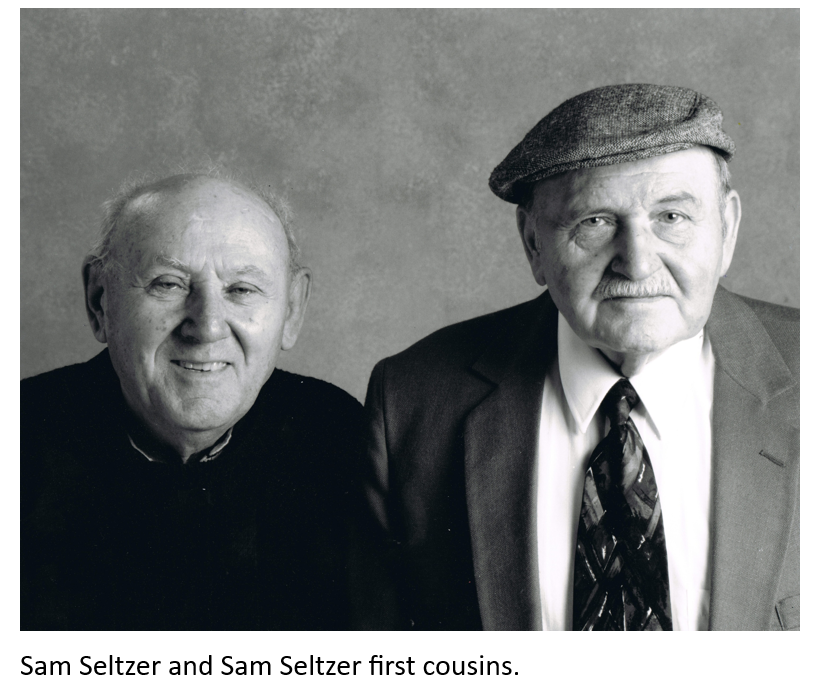

Sam Seltzer

"Watch out for something like this to happen again."

Name at birth

Smil Seltzer

Date of birth

08/21/1925

Where were you born?

Where did you grow up?

Sosnowiec, Poland

Name of father, occupation

Abraham,

Owned a restaurant

Maiden name of mother, occupation

Ciryl Stybel,

A cook in the restaurant my father owned

Immediate family (names, birth order)

Five children from oldest to youngest – sister Tonia, sister Bronia, brother Mordchai, myself, sister Lola

How many in entire extended family?

48-50

Who survived the Holocaust?

My brother Mordchai and myself

In 1939, at the onset of the war, Sosnowiec had a population of approximately 100,000. The Jewish population accounted for approximately eighteen to twenty thousand. When Hitler’s Armies occupied Poland in 1939, I was 14 years old. As soon as the German Army arrived in Poland, the first thing they did was to burn some of the synagogues. In many cities they locked up Jewish people in their synagogues and burned the people with all the holy objects in one stroke. Synagogues that were not burned were taken over by the German Army and used as warehouses or horse stables.

Obviously maintaining Jewish traditions was more than difficult, but somehow we managed to keep our Sabbath. Kosher meat that had been slaughtered in secret was available. In some cities you could get permission from the Gestapo, to conduct High Holiday services, it all depended on the whim of the Gestapo. We also had secret volunteer staffed schools, secular and religious. Formal education and religious ceremonies were held in private homes under guard.

On September 2, 1939, the Nazi Army came to our town. The first atrocity inflicted upon the Jewish population was perpetrated on the elders of my community. The elders were singularly taken by the Nazis to City Hall and there they were summarily shot and killed. The Jewish population believed that these orders came directly from the front line soldiers, Storm Troopers, not from Nazi Command Headquarters. The elders were killed in order to shatter families, disrupt communal organization, to initiate shock and fear; to terrorize.

A short time passed and the Nazi Police and the Gestapo replaced the Storm Troopers. They organized and exercised brutal power. Their first command moved the Jewish population from the newer part of town to a much smaller area. This order stayed in effect until the entire Jewish population had been moved to the old Jewish area, with Nazi control over the Jewish people. The Ghetto in our town was not a fenced in area with a watch tower, like in some other cities in Poland. We had already lived in the area which became the Ghetto, so we were allowed to stay in our home. From the time the German army marched into our town until I was sent away to camp, we were allowed to stay in our own house. But there was no more open market, no more restaurants. Eventually, the Germans revoked all property and business rights outside the Ghetto for all Jews.

In the spring of 1940, we were ordered to wear an armband and a badge on our coats. We wore the Star of David as an insignia of our Jewishness. To be caught without an armband would mean punishment by jail, a large fine or even death.

Harshness and deprivation were facts of life in the Ghetto. Survival was at a premium. Within the Ghetto, a “puppet Jewish administration” was installed by the Gestapo. In reality, all phases of life and death were controlled by the Gestapo. Directives were ordered to the Jewish Council members by the Gestapo. Failure to carry out their orders sanctioned immediate capture of Council members by the Gestapo. The Council members were held at Gestapo headquarters until the orders that were issued were carried out. Conditions in the Ghetto deteriorated as the days passed. New directives were common occurrences. For example, any Jew found outside the Ghetto looking for work or any means of survival, would be captured, taken back to the Ghetto and hung in public. I witnessed this many times. Many, in fact, died in this fashion. I never ventured outside the Ghetto after these orders were issued, except with German permission.

In the summer of 1940, the younger men in this Ghetto were ordered to report for work assignments. Some of the jobs assigned to us were; working in the coal mines, building roads, and various other construction related activities. My brother and I were given paying jobs of sweeping the streets in the summer and snow removal in the winter, in the part of town where only Germans used to live. We had special papers from the German Authority, so we could travel to do this work. We also had special permission to travel on the train to Katoviec, a German city, to do sweeping and snow removal, but we always had to have the yellow star on us. My two older sisters worked in Sosnowitz in a sweat shop sewing uniforms for the Nazi Army.

Our wages were meager, but my family was together and this union provided the little joy that helped us through these times. There were opportunities in homes for worship with others, but these we always held in secret with someone watching outside. Those who were working were given extra bread, which we shared with our loved ones. We also used the extra to barter with the Gentile population for food and for other things that a person needs; like medication or other items that were not available in the Ghetto.

Since the Ghetto was not fenced in some Gentile farmers smuggled in food, chicken eggs, etc. You only had to have money, clothing, furniture or other valuable items which could be bartered. Also, a lot of Jewish people used to leave the Ghetto to buy food or do some work for farmers. We would supplement our Ghetto possibilities by exchanging our services and skills. Sometimes we had to remove our identifiable yellow stars to dour our barter facing the outcome of 1) not wearing the star and 2) doing unapproved work.

In 1941 the men were ordered to report to the Nazi Police. They informed us that we were being transported to Germany for work assignments. We were promised our pay would be good and we would be able to go home every six months to vacation with our families. Many men voluntarily reported to the German Police to work in Germany due to the deteriorating living conditions. Food rations became increasingly scarce and housing was filled beyond capacity. My sister Tonia, her husband and daughter Reila came to live with us also. Jews from surrounding areas were shipped to our Ghetto. This overcrowding created competition for housing and all necessities.

Information filtered back into the Ghetto from the men who went to Germany for these work assignments. They reported that they had been assigned to build camps for us. When a camp was completed, the Gestapo was ordered to fill it. News quickly spread that the camps were to be filled with Jews so the men no longer willingly reported to the German authorities.

Fortunately, not everyone hated the Jews. News came from couriers who were Gentiles, Poles or Germans. They were not accepted into the Army because they were too old. They came into the Ghetto with letters from the camps. They were paid with any kind of valuables that were available; clothing, furniture, watches, gold. Because of their ongoing efforts they took letters back to the camps.

At night the S.S. would surround a section in the Ghetto and capture all the Jewish men that they could find. A list was provided by the Jewish council. The S.S. used giant lights so they could see everything, but the lights blinded the subjects. The Jewish Police were sent into your home with names. If the man was there, they marched him out into the street, where all the men were assembled. When they had all the men from this section they were marched to a holding place where they were held until they had enough to fill a train. If they could not get enough people in our town, they did the same thing in other towns, until they had assembled enough people for a specific camp. If the S.S. could not locate the named young men of the house, they would hold the entire family as hostage at the police station. The families remained hostage at the police station until the men reported for shipment. This was their way of coercing what they wanted, another form of intimidation. Finally one night in June 1942, our section of the Ghetto was surrounded by the S.S. By now, my father (may he rest in peace) suffered a heart attack and passed away. It had become transparently clear that the Jewish people were no longer being transported for just work assignments.

When someone died, all we could do was to transport the dead to the cemetery for a burial service. 10 men are needed to create a quorum; and that was the total allowed to attend. Shiva could be observed with the requisite in the morning, and at night, with a scout outside. As Orthodox Jews we were hoping for a miracle, but it did not arrive until six million Jews had been annihilated.

The population of the Ghetto was rapidly shrinking and the youth were almost entirely gone. A handful of young were kept in the Ghetto to perform the necessary tasks ordered by the Government of Germany. Nightly raids and shipment of our young men and women continued until 1942. At that time a new order was given – families without men were ordered to register with the Nazi authorities. The people were told that they too would be shipped to Germany to be “re-united with their husbands and sons”.

In the fall of 1942 my older brother, Mordchai, was deported to a camp in Germany. We did not get letters from him, as it took time to be hooked up with a courier. I remained in the Ghetto with my mother, three sisters and one niece until February 27, 1943, when we received my notification to report to the German Police to be shipped out. The remainder of my family remained in the Ghetto in Poland until October 1943, when the Ghetto was “liquidated” and everyone was taken to Auschwitz. (Before the liquidation, my sister Tonia and her baby left the Ghetto and went to another small town about 15 miles away. They stayed with a German family that our family had known before the war and she worked for them in their bakery. I learned this after the war.)

Reports filtered back to the Ghetto from the camps telling of deplorable conditions and the daily atrocities. Guards beat our men to death and this news was quickly spread around the town. Our people did not want to believe that the German population (which possessed an enviable cultural heritage) would massacre any of my people. We had felt safe with non-Jewish people because they had known our family for a long time. We lived in the area for more than 100 years.

I was in a holding area for 3 days and on March 2, 1943, I was deported to a labor camp in Oberlazisk, Germany. We were only allowed to take some clothes with us. We were all men except for about 12 women. The oldest person was only 50. This was only thirty miles from my home. Correspondence with my family was strictly forbidden. I worked at an electric power station in this camp. The work was extremely hard and living conditions within this camp were very primitive. The food that the Nazis provided was meager and we worked a twelve hour day. Many were precariously weak and susceptible to disease. Contagious diseases were prevalent within the camp due to highly unhygienic conditions. During this 8 month stay at Oberlazisk, sick people who could not be treated in camp were sent to the hospital in Sosnowiec. The dead were also sent there, but there were only about six who died at that time. Work was conducted under the watchful eye of the Verhmacht, which is the regular army; this camp had not as yet come under the command of the S.S. I was 18, but there were others as young as sixteen.

Being at this camp, I came across a Gentile man, Stasiek Kaczmarek, who was working there as an electrician. I used to go to school with him. He used to travel home daily, so he would tell us what was going on with our families. He used to know who was shipped out daily. He also brought clothing for some of the people. Food was not available in the Ghetto, but he brought us letters from our dear ones.

I had a good job. I adapted; I became a carpenter making forms for the cement crews. The Head in camp itself was a Jewish man, Motek Joskewicz, and it just so happened that he was related to me, so life in that camp, for me, was bearable. He used to help me with an extra portion of food and other necessities.

One day I got a letter from home with a page for Motek from his brother. His brother was asking him if he could help him to come to Motek’s camp as he was expecting to be shipped out any day. This would not have been an easy thing to do, but he knew that Motek had some influence. I can’t say if he tried to help his brother, but he expressly told me he didn’t want to receive any more mail from home. He was with his wife a German Jew. She was a very fine person and she helped me as much as she could. Was Motek kind to the other inmates? I must say no.

We stayed in this camp from March through October before we were evacuated to Auschwitz. Our High Holiday arrived, Yom Kippur. Officially we could not celebrate, but we did conduct service as best we could. We did not have prayer books, but the older people wrote down what they remembered on little scratch paper so everybody could pray. On Yom Kippur we were fasting, and when we came back from work, we conducted our service, after that we ate.

One morning in October 1943, we were awakened and taken to waiting trucks standing outside the camp grounds. We were ordered to gather our belongings, which were not very much, and board the trucks. As this was our first camp, we had some clothes which we had brought from home. We were trucked back to Poland. After 1 hour we arrived at the concentration camp Auschwitz!! Auschwitz was the German name for the Polish city Oswiencien, its name today. At this fateful point I realized I was no longer at a work camp; I had arrived at the “Final Solution of the Jewish Problem”.

As I was leaving the truck the first thing I saw were the S.S. men with vicious attack dogs positioned everywhere. I was ordered to remove all of my clothing and went through a selection process in the nude. This process was ostensibly to determine the well from the unhealthy. An S.S. man stood in front of me as a Dr. Mengele took a quick perusal of my body for any blemishes or weaknesses. Then the S.S. man ordered us either to the right or left. I was sent to the right. Immediately my left arm was tattooed with a number, 160282, and I was then ordered to enter the camp. Once inside my head was shaved, I was given a blue and white striped uniform, a pair of wooden shoes, and assigned to a barrack. Those who were with me on the trucks and ordered to the left, I never saw again. I found out a short time later that they had gone directly to their deaths via the gas chambers. The smell of burning flesh permeated the air of Auschwitz. From this point forward I was no longer a name, but a number.

The shoes we were given had 2 straps across them and our fee were always slipping as they were not sized. We got a new blue and white striped outfit when we arrived at Auschwitz. It had the number which was tattooed on our arms. The only way to have an extra uniform was from a dead person, but then it would be a problem as to where to keep the extra uniform there was no storage. In the summer you could wash your uniform with cold water and dry it outside, but you had to watch it so nobody would steal it. This could be done at night or on Sunday. This is one reason we were susceptible to disease, typhus, lice, etc. Some people never washed then lost their will to live.

Life at Auschwitz was a constant bombardment of death and inhumanity. Atrocities and humiliations were inflicted upon the prisoners by the S.S. continually. The presence of death was everywhere. The dead were not buried; they were gassed and cremated in the crematoriums or cordons inundated in pyres. The Jewish faith teaches that a person comes from dust and goes back to dust through burial, never cremation. Traditionally, when a Jewish person dies, the dead are handled by a group of people who are doing this as Mitzwa, a great deed, a blessing. Their duties include cleansing the person, cut and grooming the dead, and dress him in white sheet (a male would also be dressed with a prayer shawl). The dead are cleansed to be pure and holy to meet Lord God. None of this happened in the camps.

Typically I was awakened at 5:00am, ran to the washroom to wash with cold water, and then back for a cup of black coffee and one slice of stale or moldy bread. I was then ordered to assemble outside the barrack for roll call. The S.S. checked each morning for escapees and how many prisoners had died during the night. Each morning we carried out the dead prisoners, but first we stripped them of clothing and shoes which we portioned out to be kept or traded.

The barracks had bunks of wooden shelves that were three deep. Each bunk was intended for one person, but with the influx of so many inmates, we slept three or four to a bunk. We were provided with one blanket and a little straw. Many times I would wake up to find that one of my bunkmates had expired during the night. All who were sleeping in the bunk had to take the body outside for roll call so that the body could be accounted for. We would try to say a prayer before we took the body outside. Later in the day a group of inmates pulling a wagon would gather up the dead and take the corpses to the crematorium or pyres. Sometimes when we gathered the dead, we would find a slice of stale bread or better yet a pair of shoes. The inmates and I would fight over these treasures (anything to live a moment longer). Each barrack had a pot bellied stove, but we were not supplied with any fuel. Our game on how to survive one more day was to outsmart the Nazis. Many people at Auschwitz would walk to the fence, touch it and be electrocuted; deliverance. Some were shot by the S.S. before they even reached the fence. I was not in Auschwitz too long.

After the morning assembly everyone was ordered to a work detail outside the barracks. This process of assigning jobs took many hours. Since the prisoners did not possess any winter clothing standing outside in the winter temperatures made our ordeal worse. Work assignments consisted of constructing new barracks for incoming inmates or for the S.S. guards or road construction and cleaning the camp. Other assignments were meaningless, humiliating and degrading. This is exemplified by inmates digging ditches, carrying the dirt in the back of their jackets from one end of the camp to the other, then back again to dump the dirt in the same ditch they originally excavated if from. We were made to move with great urgency at a fast pace and prisoners were always observed by overseers or an inmate foremen called at Kapo. The overseers were either German political prisoners who advocated policies against the Nazi’s or many were simply social outcasts. Most of the Kapos, or overseers, were Christians, but there were Jewish Kapos and they too were very brutal. Beatings were commonplace especially if a prisoner did not perform a work function “properly”. Each and every day we would bring back a few friends who had been beaten to death. We had a will to live by hoping the next day would be better.

At noon I was given a cup of soup made of potato skins boiled in water. That was all the food received until we went back to the barracks at approximately 5:00pm. Again soup and a slice of stale bread were rationed to the prisoners. We carried with us a canteen to put the soup in and a spoon in our pocket.

When I left for work in the morning and when I arrived at the gate at the end of the day we went through the agony of counting. As we walked through the gates we would also hear music that was being performed by the inmates. After this I would run to the washroom once again to wash with cold water and then assemble again outside the barracks to be accounted for. If everyone was accounted for, we were permitted to enter the barracks and climb into our bunks to escape the elements and keep warm. But one was never to escape the element of death! In my bunk the thought that the most elementary force, death, had been evaded once more. For “entertainment” we would talk about how life had been before the war. Lights were turned off at 9:00pm.

The Nazis did have lists of people and they kept some record of the people who died. There is a list now at Auschwitz. I looked at the list and found my wife’s name and her sister’s and the date they arrived. I looked for my sister’s name but forgot to look under her married name. There are a hundred books of lists.

At Auschwitz the mix of people varied from Jews, Christians, Gypsies, clergy, Polish intelligence and many different nationalities. Inmates came from all of Europe and everyone brought news of the outside world. The only thing I wanted to find out from new inmates was where they had come from and how the war was going. I learned that I was in the largest annihilation camp in all of Europe.

The job of cleaning the barracks was a great privilege and you were lucky to get the job. This was not my job. Mostly it was given out to a relative of the man who was in charge of the barrack. Each barrack had a person in charge, a “stuben elster” or room elder.

The latrine was the only place where we could meet and talk with all kinds of people from different countries and different states. While sitting on the latrine one day, a man approached me and asked if I was Sam Seltzer. I didn’t recognize him, but he said he was Israel, a nephew of my mother’s. He was married to my Aunt Dora’s daughter Rivcia. He was from Zawiercie. He witnessed what happened to my mother’s sister and her family. They all perished in Auschwitz, 10 or 12 people in all. He was the only one left and he didn’t look like a real person anymore. This was the only time I saw him.

I met some prisoners from my hometown and they provided me with tidbits of news of my family and friends. I learned that the Ghetto had been liquidated in October 1943. The entire population was deported to Auschwitz and the majority sent directly to the gas chambers. I never saw my family again except for my brother Mordchai. When receiving bad news and living a hard life all the time I had become hard as iron, sad news bounced off my metal.

As time passed I realized the only fate waiting for me at Auschwitz was death. One day I ran into a friend, Moses Gutman, from my hometown. He came to Auschwitz with all the families from my town, who were there after I left in 1943. I asked him what will happen to us in this camp. His answer was that I must register anytime that there is an announcement for people to be shipped out to any place. He also told me that if I didn’t get shipped out the only other way out was through the chimney. He helped me a little with food, which was very much appreciated. He had a good job in camp. Also, he was safe because he had found a man who was an anti-Nazi German and their families had known each other before the war. This anti-Nazi German used to come to our town to buy horses on Thursdays. He helped Moses with everything he needed; a job, clothing and food.

Moses told me he heard the Germans were looking for construction workers to be deported to other camps. The workers were not to be Polish Jews. Only French, Dutch, Greek or Italian Jews could register for these jobs. I knew that I had to leave Auschwitz, so I registered as a Greek Jew. As all we spoke was Polish, German and Yiddish, I felt I had outsmarted hem when I was accepted. Greek Jews did not speak Yiddish and only a little German. I was transferred to another barrack to await deportation out of Auschwitz. When I entered the new barrack I discovered a few friends that I had been with at Oberlazisk. They too were Polish Jews who had falsely registered and escaped immediate death at Auschwitz. Moses did survive Auschwitz, until the camp was liquidated in the fall of 1944, when he was shipped out to Lansberg am Lech in Germany. Later when I was in Camp 7 he was in Camp 8. Another friend of mine, Joe Buda, came across Moses while on the job and they started to talk. Joe asked Moses where he was from and when he said Sosnowiec he asked if he knew me, of course Moses said yes and asked for help with food and some clothes. Since I was working with Heinz and also had a friend working in the kitchen I always had extra food that I could use for bargaining.

At night Joe came back from work and told me about the conversation. Thanks to God I was in a position to help pay him back for saving my life at Auschwitz, so I sent something through Joe to him every day. I could not see Moses then, but I ran into him in Munich in 1945 after liberation. Moses left for Australia in 1948. He died in 1990.

I was confined to the barracks for three days while waiting for a train to be emptied of new arrivals at Auschwitz. This cattle car was my transportation of the camp along with approximately 4,000 other prisoners. Each prisoner was given a loaf of bread that weighted about a pound, one can of meat and a blanket. Sanitary facilities consisted of two buckets. Drinking water was dispensed by one man from a small barrel. Each prisoner received the same amount of water. As the train left Auschwitz late October 1943, none of the inmates knew our destination. I had been in Auschwitz only about 10 days, thanks to God.

Conditions in the cattle cars that were used to transport us were unbelievable! There were many fights among the prisoners over rations, but I was one to try to make peace. Some prisoners at their rations too quickly and then began stealing other prisoner’s rations. The salt content of the canned meat was very high and made everyone very thirsty. Water was in short supply and did not last. The buckets intended for sanitary purposes were always full. Many died on this trip and the corpses remained where they were in the cattle cars. We traveled this way for five days. It was about 120 miles from Auschwitz to Warsaw. Before the war the only place I had been to was Zawiercie to visit my mother’s sister. We traveled by horse and buggy and it took us 8 hours.

Eventually, the train stopped and we were ordered to disembark. None of us had any idea where we were, but looking around us as far as the eye could see there was nothing but rubble. Again, everyone had to be accounted for, including the dead. The dead never received a decent burial; they were burned with wood from the rubble. After the accounting we were ordered to walk. As we walked we noticed signs in Polish. After about a half hour we stopped at a cleared area. There were already some wooden barracks here and this site became our new camp. The next day we were assembled and counted. They asked for tradesmen so I volunteered as a carpenter and we started to assemble the barracks. After about one week we could like in the barracks at night on the ground. At least it was warmer, as we had been sleeping outside huddled together for warmth. The nights were cold, but luckily I did not freeze. I had learned the best and only way to survive within the camps was to be a tradesman. Those who were assigned to work outside the camp brought back the news. I learned through these workers that I was in Warsaw, the center of the largest and worst Ghetto in Poland. It was 4-5 miles long and 10-15 miles wide. The reason for all the destruction was that we had arrived there after the now infamous Ghetto uprising. Nothing was left standing for as far as the eye could see, just chimneys.

The camp took about 4 weeks to complete. Afterwards, everyone was assigned work outside the camp. I was assigned to work with ten other prisoners to clean up the rubble of homes in the Warsaw Ghetto, always under the watchful eye of one guard. The ferocious battle that raged between the Jews and the Germans left the entire Ghetto in rubble. Not one single home was intact.

We were ordered to salvage wood from the rubble and this we used for fuel for cooking in the kitchen for the S.S. and inmates and to cremate the dead. What was left, or what we were able to steal, we used in the barracks for heat. The dead were never buried, we would find the bodies and pile them one on top of the other and then set fire to the wood to cremate these bodies. To have refused to do this would have meant being shot on site, so I did as I was told so as to survive one more day.

While working in the Warsaw Ghetto my group met another group of Jews who were prisoners at Pawiak. They were under guard by the Polish Police. Pawiak was a jail that was left standing in the Ghetto. These prisoners were doing the same salvage work that my group was assigned. As we talked with them we learned that they were from Warsaw and had survived the Warsaw Massacre by hiding in the underground bunkers. They were forced out of the bunkers by fire bombs and were caught by the S.S. troops. Some of them gave themselves up when they ran out of food and water. They told us that there were 200 Jews at Pawiak who were captured after the uprising had ceased. We learned that not all of our people were herded off like sheep to be slaughtered. We were very proud of the Jews who we learned fought to the last man against the Nazis in the Warsaw Ghetto.

The Pawiak prisoners proved to be invaluable friends as they knew the Warsaw Ghetto very well. They were able to tell us where to find food, clothing and other necessities. Their knowledge encompassed every home that was in the Ghetto. They had all kinds of connections. They used to give us a bottle of whiskey for our German guard and our Kapo so our supervision was sabotaged.

We found where the underground bunkers connected one house to the next. These started out as basements in the houses and then resistance fighters dug to connect them to each other. Most of them had secret compartments where we discovered food, water and blankets. We were able to take small things back to the barracks in our pants pockets and they became valuable to trade for food. As we explored these bunkers further we found many dead bodies, entire families in some instances. They appeared to have been killed by poison gas. The Germans had blocked the exits from these bunkers and there was no escaping the gas the Germans used.

In further conversation with the prisoners of Pawiak, we gained greater insight into the Warsaw uprising. Children found the Nazi Army right alongside their elders. If the Polish, non-Jewish, population would have taken up arms against the Nazis or helped with the uprising the fight would have lasted much longer than six weeks.

One day as we were going to our job of looking for wood we stopped at the Pawiak prison. Seeing a man looking out the windows I started a conversation with him. He asked me where I was from. I told him my name ant that I came from Sosnowiec. What a coincidence, his family came from the same town. So I asked him his name and he said Igra. I asked him if Aizia Igra was a relative. He said yes, his father’s brother was Igra. Igra was married to my father’s sister Lea. He said he knew who I was and asked if I knew anything about his family. I said that I had just heard from a friend, Najer, two weeks earlier that he had seen one of the family, Janka Igra, walking in Warsaw as a free person. He didn’t talk to her so as to not give her away. I knew that my cousins were somewhere in Warsaw as Gentiles, but didn’t know where. I knew one of my cousins, Jurek, went to Chenstochowa Ghetto while I was still home. He was to have an operation on his penis so he could be seen as a “real” gentile. By having this operation on himself, he saved his wife, two more brothers, three sisters, two of their husbands and one child. These were 2 households that had papers as Christians. Jurek and Stephan were brothers, two of Lea’s 8 children. Jurek married Sonia, Stephan married Janka.

One day as we were going from house to house to gather whatever wood we could salvage we came across two Jews hiding out in one of the skeletons of a house. One man from our group tried to climb up to the second floor to gather wood to throw down to us. When he reached the second floor he was stopped by the two men with a gun. They spoke to him in Polish to stop and get down and to not say anything about seeing them. As he climbed down the Kapo with us, a German, asked what was going on up there and ordered him back up for the wood. The two men in hiding heard this and came forward with the gun. They shouted in German to disappear and then started to shoot. The German S.S. got us away from the house and started to shoot into the house. When the men did not respond he got help from the other S.S. men that had heard the shooting. They surrounded the house and tried to get them to surrender, but what they got was a hail of bullets which lasted maybe 5 minutes. About two hours later we heard an explosion. The Germans dynamited the remaining portion of the house, but I am sure that the men went through the sewer to the outside Ghetto and survived. The sewer was the highway out of the Ghetto. I was proud of them. They must have had connections with the outside to be able to survive. Why they were there I do not know. When we would find clothing, pots, pans, or any valuable item we used it to barter with the Gentiles for food and whisky. We would give the whiskey to the S.S. to get them drunk, impair their diligence.

As time passed by, after a few weeks, we noticed that we had not seen the commandos (prisoners) from Pawiak Prison who had been so helpful to us and we wondered what had happened to them. So we tried to walk by the Pawiak Prison hoping to find out where they were. As I mentioned before they were doing the same job we were, looking for wood to salvage. Their wood was used mostly to burn Polish Christian underground fighters who had been caught throughout Warsaw. When the fighters were caught they were brought into the Ghetto, which was next to the Pawiak Prison. There was a long wall of an apartment building which was still standing. The fighters were put up against this wall, blindfolded and shot by German Gestapo. They lay on the ground for a while until nobody moved. The Jewish Commando (prisoners) from Pawiak started to remove any valuables the fighters had on them. If any had gold teeth, they were pulled out and the Germans took all the valuables and the clothing if it was in good condition. The bodies were put together in a pile and wood put around them and the bodies were burned. That was their job.

In talking to the man in the window at Pawiak we learned that all the ten men from the Commando disappeared. What happened to them nobody could verify. The Commandos had told us that they had contact with the underground and maybe they joined them. The prisoners at Pawiak were punished and all were shipped out. We assume they were sent to Auschwitz. This was in the summer of 1944.

After a while we came across a Commando of Jews who was lodged in Pawiak again. They took over the job from the last Commandos. As we started to talk to them we found out they were brought from the Ghetto of Jews in Lodz, who are working for the German Army making uniforms. Conditions in the Ghetto were very bad. People were starving from malnutrition. Food was rationed and they felt they were lucky to be brought to Warsaw. We didn’t have help from them as we had from the previous group; they needed help from us. What ultimately happened to them I don’t know.

During our work throughout the Ghetto we also came in contact with the civilian Polish population. Some of these meetings were not pleasant. They would buy the material, steel, brick, windows, doors, that we salvaged from the ghetto homes. We would load these materials into their buggies that were pulled by horses. The material was sold by the Nazis.

Since some of us spoke Polish we found out about life outside of the Ghetto. We bartered with these people for food by using some of the valuables we found in the ruins, pots, pans, dishes, civilian clothing. They would promise to bring us food the next day. Most of these Polish people did bring us food, but many did not. We could not report them; report to whom? The Nazis?

As I stated earlier I came to Warsaw with approximately 4,000 other prisoners as a “Greek” national, but once in place, no one asked your nationality. We remained in Warsaw for about ten months before we were again evacuated. During this ten month period thousands died. Malnutrition, exposure to severe weather conditions, and a typhoid epidemic claimed many lives. Curiously the Jews from Holland were the first to die, followed by the Italian Jews, Greek Jews and finally the French Jews. Because typhoid is highly contagious it wasn’t long before I had contracted it and had my own battle with death. The fever claimed lives by the dozens each day. To this day I do not know how I survived without any medication. I remember breaking icicles off the barracks and licking them to cool my high fever. In approximately 10 months, 2,800 prisoners died, leaving about 1,200 of the original 4,000 that I arrived with in Warsaw. The camp was quarantined for awhile because of the typhoid epidemic.

One night in August or September 1944 we heard a lot of plane noise at our camp. Then we heard sirens. The whole camp was lit up by the planes as they were flying very low. We ran out of the barracks not to run to any shelter, but just to sit on the assembly place. We saw the planes were Russian. They did not shoot at the camp, but we heard explosions that lasted about 2 hours. Since we were all at the assembly point we were told to stay there because we would be leaving Warsaw first thing in the morning.

On the day of our evacuation of Warsaw, the non-Jewish Polish population rose up and took up arms against the Nazis. The 1,200 of us that were left were ordered to walk north, we walked for three days.

During the three day walk many people either died or were murdered by the Nazis. The prisoners that were too weak to walk fell down and the Nazis shot them right on the spot where they fell. The bodies were thrown to the side of the road, not even cremated. After seeing this daily, one loses any sense of outrage. As we were passing through a small town I began talking to a girl in Polish. I asked how far it was to the river. We usually stopped overnight by the river to wash up and drink our fill. It was getting late in the evening. The next think I knew I lost consciousness. A soldier had taken the butt of his rifle and hit me in the back because I was talking. A friend had a bottle of water and was able to revive me. If he had not, I would have been just another corpse on the side of the road.

On the second day of this forced march we came to a town and were ordered to board a train made up of cattle cars. As we boarded we were given a slice of stale bread and a small can of meat. We were packed eighty to one hundred men in a cattle car. The water ration was one-half cup per day. The canned meat was extremely salty again, making water a most precious commodity. There was only room enough to sit up and we slept on top of each other. One bucket per cattle car was provided for everybody refuse. In order to service eighty to one hundred people some of us ripped out a few boards of the cattle car so the opening could be used for refuse. Our destination was still unknown to us. On the third day we passed several train stations with German names. We then knew we were traveling in Germany. We traveled for three more days until the train was halted and we were ordered to disembark. We saw quite a few S.S. soldiers and prisoners. The first thing we asked the prisoners was our location. We learned we were in Dachau. When we arrived in Dachau, only 550 -600 of us remained alive. In three days more than 600 people had died. Dauchau is in Bavaria Germany. The camp was named after the city.

As we entered Dachau we saw a sign that had been erected that read “Arbait Macht Frei” (Work Makes You Free) and “Faulhalt Macht di Knocken Steif” (Laziness Makes Your Bones Stiff). The camp was smaller than Auschwitz. This time music was not being played as we entered. The camp commander at Dachau, who was a German citizen and a political prisoner, initially instructed the prisoners that our stay would be short. A new camp was in the near future for us. After the commanders greeting we were ordered to the showers to bathe and given new clothing. Assignment to a barrack then followed. Curiously Dachau assignments were not as harsh as Auschwitz. There were no abuse to our bodies; prisoners were not immediately sent to the crematoriums. The inmates ran the camp and many were German prisoners. The German prisoners were incarcerated for political activities. They acted as the Kapos and they were not as brutal as the Kapos in the previous camps I had been in. I was able to rest for approximately five days in Dachau. Eventually a passenger train arrived and I was shipped to Landsberg am Lech. The trip from Dachau to Landsberg was just a short trip about four hours. We walked about one more hour through the city until we arrived at a forest with a wire fence. Nearby were barracks for the S.S. troops. (Note: Landsberg is the location of the prison were Hitler wrote “Mien Kampf” while incarcerated)

In Landsberg I was assigned to help build the barracks. The camp was to be located in this forest which land needed to be cleared. The barracks were designed to be built four feet underground and four feet high. We were instructed to camouflage the barracks with dirt and sod. By creating berms the buildings had sufficient insulation. When the barracks were completed most prisoners were assigned jobs outside the camp. We would walk 2 – 5 kilometers from camp. Construction of the barracks continued even though housing for the prisoners was completed for the 1,000 people I came to camp with. Most of the prisoners were assigned jobs outside camp to build ammunition factories thus explaining the camouflage technique. Working conditions in the factories were brutal and many prisoners were near exhaustion levels. Exhaustion resulted in many deaths. The corpses were buried for the first time since I became a prisoner. I stayed in camp and came to know a German citizen, Heinz Helbig. He worked as a sheet metal man in the heating of the kitchen. He asked me if I wanted to become his helper and he could ask for me from the S.S. I accepted and received a work assignment to work with Heinz as a heating helper. He belonged to the Communist party and was forced to labor for the German Government away from his home. He was not locked up. He was living with the S.S. outside our camp, but he was not allowed to leave the camp without permission. Once I got to know him he told me he was from Leipzig where he had a wife and two daughters who were still at home, but he was not trusted. His assignment was to work in our camp.

This man helped me to remain alive by bringing me his extra food. I was able to pass some of this food to the other prisoners. He had a large food ration to begin with and he also received food packages from home. I worked in the kitchen some times and while doing this I got friendly with a man from Frankfurt am Main, Kurt Kutz. He was from a mixed family, his mother being Jewish and his father Gentile. In early 1942 he and his mother were taken to Auschwitz. That was the last time he saw her. He stayed in Auschwitz until 1943. Because he was German he had a job in the kitchen as a Kapo. When he found out they were looking for men to be shipped out he decided to join that group. He was in the same group that I was in when I was shipped out of Auschwitz. I had known him there, but not personally.

One day Kurt asked me if I could do him a favor, speak to Heinz and see if he would be willing to mail a letter for him. Heinz said yes, so the next day I took a letter to Heinz. In about 2 weeks Heinz brought me a letter from Frankfurt am Main for Kurt. It was from a girlfriend who was Jewish, but had false papers as a Gentile woman. She was hiding out in Frankfurt am Main with her father. I found out that she was asking Kurt if it would be possible for her to visit him at Landsberg am Lech. He gave me the job of talking to Heinz to see if it would be possible. We wanted to arrange this, but we also didn’t want to jeopardize Heinz’s life, hers or our own. We worked up a plan on how to do this. She will come to see Heinz in his barrack as his niece if someone asked. My job was to get Kurt out of camp, since I could go in and out without any problem. I just had to report to the watchman where I was going and why. I would report that we needed a special thing for the kitchen. The story was that Kurt was the Capo for the kitchen and he knew how to make the special thing and he needed to go to our shop to show us. All of the S.S. knew him so there was no problem getting him out.

Kurt wrote to her about the plan, but it was up to her if she wanted to risk a visit. One day we got the news of when she would be arriving. When the time came I reported to the guard that we needed Kurt out in the shop. The shop was right next to Heinz’s barrack so no one saw us. She spent about one house and was pleading with him to escape from Landsberg am Lech to go to his father’s brother in Nuremberg. As this uncle was a Nazi, Kurt said he didn’t want anything to do with him. She also pleaded with him to be kind to the other inmates and to try to help if he can. While she was there she saw a group coming back from work and how they were looking. She was living with her father and brought a lot of gifts for Heinz’s family. She also brought chocolate, oranges and other fruit that I had not seen for years. She also brought some clothing for Kurt, but the only things he took that day were a sweater, woolen socks and a watch. After an hour she left and Kurt and I went back to camp. The next day it was my job to bring some of the items into camp. I had a small wooden tool box and little at a time I brought everything to Kurt. He was very thankful to Heinz and to me. Kurt survived and went back to Frankfurt am Main. I have not seen him since, but I know that he left Germany for the United States. He was in Cleveland for a while, but where he is now I don’t know. I tried to contact him there, but he had moved. He did marry this girlfriend.

A few months passed at Landsberg and new prisoners arrived. The prisoners came directly from Hungary and some from Auschwitz. Mixed in with the new arrivals were females. The females stayed in camp, but they were separated from us by wire fences. Their work details included cooking, cleaning and laundry in the S.S. guard’s barracks. Uniforms were provided for the women. They were blue and white striped dresses, a pair of wooden shoes and their heads were shaved. One day Heinz and I were sent to the women’s section to repair the chimney of the pot belly stove they used for heating. I asked some of these women questions such as where they were from. They also asked me for information about relatives and friends and were very frustrated not knowing the whereabouts of these people. They had been in Auschwitz only long enough to be transferred to another train and brought to our camp. Most of these women were from Hungary or Romania.

One woman, Eta, from Romania asked me to see about getting a pair of shoes for her sister. She worked in the S.S. headquarters as a cleaning lady and was able to offer me cigarettes and food in exchange for the shoes if I was able to find some. I found a pair of shoes that had once belonged to a prisoner who had died. The people who arrived direct from Hungary had shoes the rest had wooden shoes. She thanked me many times over. She became my girlfriend and eventually my wife. We are still friends to this day.

Once again prisoners who worked outside the camp gathered news and information from inmates in neighboring camps whenever they came in contact with them. They exchanged names of relatives and friends and in this way I was able to learn that there were approximately ten camps in the surrounding area. In the winter of 1944-45 a new arrival from Auschwitz told us of a prisoner uprising at Auschwitz. The uprising began outside the crematoriums and many were killed. Ovens were destroyed and soon after the evacuation of Auschwitz began.

News filtered into the camp that the Russian Armies were advancing from the East and the Allied Forces were approaching on the Western Front. Each day English airplanes raided the skies over our camp. The joy of seeing these airplanes did not relieve the pain and suffering. Prisoners continued to die by the dozens daily. The new arrivals died the fastest due to their weakened conditioned; they had been traveling from Hungary for weeks. Cattle trains continued to arrive for weeks.

Around April 1945 the camp was assembled and we were ordered to move to another camp, camp number one. I had been in camp number seven. Camp number one consisted mostly of Lithuanian Jews. My stay at camp one was for one day. We were assembled to listen to a representative of the Red Cross. We were told that soon we would be free!!!! The only person with the Red Cross man was the head of the S.S. He did not speak and there was no reaction from him. We were very happy that finally the day is coming to be free. We did not show any joy in public and to tell the truth a lot of our friends didn’t believe what he was saying especially after we had to assemble and leave the camp for an unknown destination.

Each prisoner was given a small package containing chocolate, sardines, cigarettes and a few other small items. We each received a loaf of bread and then we marched out of camp. We marched for two and one-half days until we arrived at Dachau again. Many prisoners died on this march and many had diarrhea. The food rations form the Red Cross caused many of the deaths as the digestive systems were not use to this kind of food. Before reaching Dachau we marched through the town. This was the first time I had marched through a town in day time since being taken prisoner. The German people of the town threw bread at the prisoners causing many fights to break out among the starving prisoners and even more to die. The S.S. guard stood by wagering which prisoners would fight over the bread, but they did not use their weapons. As we entered Dachau we noticed major changes. Warehouse were opened, clothing was available for the taking but food was still very scarce. I spent the night sleeping in the open with the other prisoners. The next morning we were ordered to start marching and once again we did not know our destination. A Red Cross representative from Switzerland spoke to us before we left Dachau. Again we were given goodies, but this time we knew what to do with them.

As we marched out of Dachau I saw a train loaded with people. We were not allowed to speak with any of the people on this cattle train. I later learned that my brother Mordchai had been on this train. We continued to march for three more days. The prisoners slept in the forest at night. We all had the feeling that the war was coming to an end due to the fact that the S.S. guards did not beat the prisoners anymore. But our feeling was of caution. The sick that could no longer walk were placed on wagons and food was provided at night. Liberation was definitely in the air!!! Many more people died during this time from malnutrition and from the food from the Red Cross.

As I left Dachau with approximately 80,000 people, some of the prisoners who worked in the offices at Dachau told me that liberation had almost occurred. After about half of the prisoners crossed a bridge, the German soldiers demolished the bridge. That night I slept in the forest with the remaining 40,000 prisoners.

It was May 1, 1945 and during the night snow fell. We all became wet and chilled. The next morning when I awoke the S.S. guards were not in sight. We were afraid to move for fear the S.S. guards were waiting for us to escape and then slaughter us, but we did talk out loud. Not one of us moved. As daylight approached tanks could be seen approaching us. As they drew closer we saw the marking USA on these tanks. LIBERATION – AT LAST WE WERE FREE!!!!

Name of Ghetto(s)

Name of Concentration / Labor Camp(s)

What DP Camp were you after the war?

Yes, various throughout Germany

Where did you go after being liberated?

Immediately upon liberation, we were sent to Bad am Telz. The camp was in bad condition so some friends and I decided to travel back to Landsberg am Lech to try to find the women prisoners that we had gotten to know there. We found our girlfriends and then moved to a large camp near Munich. And then back to Landsberg am Lech.

When did you come to the United States?

June 19th or 20, 1949 we finally left for the United States.

Where did you settle?

We were told that someone from my family would be in New York and that we would stay with them for one week before continuing on to Detroit.

How is it that you came to Michigan?

We arrived in Detroit on July 28, 1949, and we were met by my uncles Willi and Harry who took us in and assisted my family with our new lives in Michigan.

Occupation after the war

My first job was driving a furniture delivery truck. I then found a job in a bakery that paid more money. I then met a plumber who offered me more money to help him. That was to be my profession for the rest of my life – a plumber.

When and where were you married?

I was married to Eta in Erfting in May 1946 in a civil service conducted by the mayor of the village. We finally had a Jewish wedding on December 25, 1947.

Spouse

Eta,

Homemaker

Children

One Daughter – Tzerl – was born on December 23, 1948, jewelry designer

Grandchildren

One grandson, Aron

What do you think helped you to survive?

Plain luck. I always came across someone that could help me.

What message would you like to leave for future generations?

Watch out for something like this to happen again.

Interviewer:

Charles Silow

Interview date:

02/28/2011

Experiences

Survivor's map

Contact us

thank you!

Your application is successfuly submited. We will contact you as soon as possible

thank you!

Your application is successfuly submited. Check your inbox for future updates.